Elearning Demystified

The Merriam Webster dictionary defines learning as the activity or process of gaining knowledge or skills by studying, practicing, being taught or experiencing something.

Learning is fundamental to human survival. From birth, we rely on a basic set of instincts, but everything beyond that—from language to culture—is gained through learning. This relentless capacity to learn sets us apart as homo sapiens; even in our most primitive state, we are required to absorb a vast array of knowledge far exceeding that of any other species.

The most effective learning occurs when a motivated individual engages with well-structured content in an immersive way, allowing them to immediately apply new knowledge within their environment. However, this process is not one-size-fits-all; it varies greatly among individuals. Some of us thrive by diving into books or articles, others by visualizing concepts through videos, many by following spoken instructions, and still others by engaging directly with the task at hand, learning through the tactile experience of trial and error.

Challenge question: what was the last thing you enjoyed learning? Describe what you learned and how did you learn it.

Recognizing the necessity of learning and understanding the elements that enhance it doesn’t inherently equip us with the ability to create the optimal learning environment.

Crafting an atmosphere that effectively motivates learners, designing digestible content, and providing step-by-step guidance demands considerable effort and expertise. This complex orchestration is a primary reason why education is a significant investment. It’s not just about knowing what needs to be learned but applying that knowledge in ways that resonate with diverse learning styles, ensuring every learner can thrive.

But what is elearning?

Elearning is still learning; but a very different and distinct kind of learning.

Elearning is often lauded for its convenience. Once content is available online, learners can access it whenever suits them best, progressing at their own pace. This accessibility significantly reduces the learning barrier for busy professionals who may not have large blocks of time dedicated to traditional learning methods.

Another key benefit of elearning is its cost-effectiveness. Unlike in-person training, which involves expenses related to instructors and venues, elearning primarily requires just a computer. From the provider’s standpoint, it eliminates the need for physical materials and labor, presenting a more economical alternative.

These two advantages—convenience and affordability—are major driving forces behind the shift many organizations are making towards elearning to achieve their training objectives.

However, as we will explore, the very features that make elearning appealing, such as its ease of access and lower costs, also present challenges. These aspects can inadvertently impact the depth and effectiveness of the learning experience, a nuanced issue we’ll delve into further.

In learning, easy and cheap are not always good words!

Elearning, in its broadest sense, refers to the enhancement or delivery of learning through electronic means. While the “e” often brings to mind online or internet-based learning, it encompasses any electronically produced content, including video or audio recordings. The medium through which this content is made available—be it hosted on YouTube, distributed via a thumb drive, or another method—pertains to the mode of delivery rather than the essence of elearning itself. This distinction underscores the versatility of elearning, highlighting its capacity to transcend traditional educational boundaries through various electronic formats.

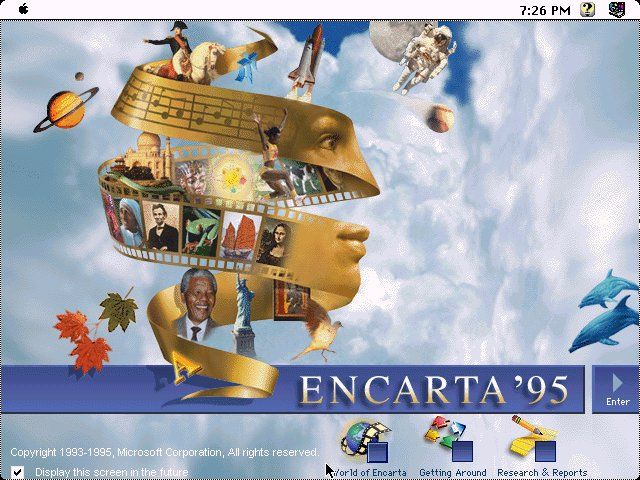

My first encounter with elearning was through Microsoft Encarta. Released in CDROM format, Encarta represents a seminal endeavor in the early days of new media elearning development. It stood as a vivid illustration of how to systematically organize information, craft user interaction, and make aesthetic decisions—all integral components of constructing an effective elearning experience.

For me, this personal encounter not only showcased the potential of electronic resources to revolutionize learning but also sparked my curiosity about the intricate processes behind designing educational content that is both engaging and informative.

This encounter with Microsoft Encarta serves as a lens through which we can view a more nuanced definition of elearning—one that transcends merely having information available online. Elearning embodies a carefully curated and structured form of learning, designed to be predominantly self-paced.

The key term here is “structured.” This distinction separates elearning from the vast array of information available on platforms like YouTube or various web forums. While these resources undoubtedly offer learning opportunities, their lack of structure places them outside the elearning sphere. Many elearning projects start with the idea of offering fragmented experiences—viewing elearning as a collection of resources rather than a cohesive course.

Self-pacing is another defining feature of elearning, allowing learners to progress at their own speed. However, this freedom comes with its challenges, notably the absence of real-time human guidance which can detract from the learning experience. The solution isn’t straightforward, but current approaches include integrating mechanisms for asynchronous support, such as Q&A forums, and tracking learning metrics in a Learning Record Store (LRS).

Ideally, self-paced learning should be one component of a comprehensive educational experience. This leads to the concept of hybrid learning, which combines self-paced study with interactive sessions, allowing for instructor and peer engagement. A popular model of hybrid learning is the “flipped classroom,” where learners engage with content independently before coming together for in-depth discussions and activities. This blend aims to harness the best of both worlds, marrying the flexibility of elearning with the rich, interactive benefits of traditional classroom environments.

What is instructional design

Elearning necessitates a comprehensive rethinking of how we approach education, requiring us to carefully evaluate the resources at our disposal and identify what’s lacking. This process is commonly referred to as instructional design—a term that, despite its widespread use, may not fully capture the depth and creativity involved in crafting learning experiences.

While the act of learning is as ancient as humanity itself, the concept of instructional design is relatively modern. It emerged from the need to systematically organize and present information in ways that enhance understanding and retention, especially as education began to leverage new technologies. This shift towards a more deliberate and thoughtful construction of educational content reflects a significant evolution from traditional, often informal, modes of knowledge transmission to structured, outcome-oriented learning strategies enabled by digital platforms.

A very brief history of instructional design

The discipline of Instructional Design, as it is understood today, has its roots in behavioral psychology, particularly in the work of B.F. Skinner and his research on behaviorism. This perspective focused on observable behaviors and the ways in which they could be shaped through systematic approaches to teaching and reinforcement.

Image on the left is a Skinner box, which is an enclosed apparatus that contains a bar or key that an animal subject can manipulate in order to obtain reinforcement.

The post-World War II era, especially within military contexts, saw a heightened need for efficient and effective training methods. The military required a way to quickly and reliably equip personnel with the necessary skills and knowledge, often under the pressure of time constraints and the critical nature of the operations at hand. Instructional Design emerged as a response to these needs, employing structured and goal-oriented methodologies to ensure learning outcomes were achieved.

This era marked the beginning of Instructional Design as a formalized field, leveraging the principles of behavioral psychology to create training programs that were measurable, efficient, and scalable. The emphasis on clear instructions, performance goals, and the systematic design of learning experiences can indeed be traced back to these military origins, making Instructional Design one of the practical applications of psychological theories in response to the operational demands of the time.

Extended Reading

If you are interested in exploring further Skinner’s theory and its impact on current instructional design landscape, you can read my recent article.

“Is Skinner Still Relevant in Instructional Design?”

Given this historical backdrop, my aversion to the term “Instructional Design” becomes clearer. It tends to downplay the richness of exploratory learning, favoring a more directive, spoon-fed approach. Yet, this is a reality we must navigate: it’s not perfect, but it’s functional.

In the conventional process of instructional design, learning is dissected and analyzed as an entity, with various strategies assessed for their efficacy. The outcomes, however, hinge significantly on the individuals involved in the project and their grasp of both learning principles and technology. This variability means that the execution of instructional design can vary widely, reflecting the diverse perspectives and expertise of those crafting the educational experience.

###Key players in the Instructional Design process

Customer: The customer or sponsor is mostly concerned with the learning outcomes and the cost.

SME: The Subject Matter Expert knows the material, or has been conducting in-person training sessions.

Learning Designer: The person who discusses with the customer & SME to determine the overall elearning strategy and design the learning experience.

Developer: The developer (could be the designer) will be authoring the course, from asset preparation (video/audio/motion graphics production) to final deployment (knowledge of LMS). The work is highly technical in nature.

Elearning dev in stages

The actual process of elearning development varies from project to project. To simplify the matter, I have divided it into several universal stages.

###1: Exploring Needs

In this discovery phase, learning designer and customer need to learn how the other party see the project and arrive on a consensus.

The designer/developer need to learn about:

the availability of assets (ppt, or graphics, videos)

the level of interactivity required

assessment needs

where should the product be deployed

The customer/SME need to learn/think about:

the timeline of project, the process and workflow, time commitment required

what would the final product do, in what general form

decision that have impact on budget (what can we afford given the budget)

The output of Exploring Needs is a Project Charter document that includes high level description of the business case, budget and time constraints, deployment requirements, and key stakeholders. Not all requirements are expected to be clear at this point and some aspects of the requirements need to be discovered or redefined after this stage.

###2: Content Acquisition

Content acquisition is an active effort made primarily by the dev team to understand what needs to be learned and articulate it in the manner amendable to elearning’s technological infrastructure.

It is basically the first step in converting “show me what you need them to learn” into “here’s how they would do it in elearning”. And there are many ways in which this can be done, depending on the unique circumstances of the project.

If the learning designer can participate the classroom training that we need to convert, or have the SME train her individually, this would be a convenient option to acquire the content.

Alternatively, the learning design can self-study. I often work by documenting my understanding of the material into a formal study note. And I will ask the SME to review my study notes and have discussion to clarify points that I am not completely sure.

Also in this stage, we can start to collect all the assets that we think that will come in handy. This includes videos, images, references URLs, pdfs etc.

The output of this stage is something I would call a Content Outline. This document would elaborate on content related issues in the previous artifact, especially in terms of readiness or efforts needed to procure them. This detailed statement of scope paints a realistic picture of what should be included and what is not. Also, it is only at this point that a realistic milestone list can be made which will serve as the framework of future iterative development.

###3: Prototype

In this stage, we want to quickly produce a concrete, demonstrable product, even if it means it looks rough, has the bare minimum of features and full of placeholders.

We are much better at generating ideas when looking at something concrete.

Writing specifications on paper is often misguided because of the gulf of evaluation.

If a project starts with some existing ppts, then a prototype can take a few slides and implement some basic forms of interaction mechanism that are appropriate for self-paced navigation. Placeholder images can be used with computer generated voiceover.

Sometimes templates can be used in lieu of designing from scratch, which is time consuming.

The output of this stage is a special prototype that we may call Product Increment ZERO. A PI0 is even smaller than the MVP because it is not shippable, but it can demonstrate key ideas in the previous two stages so everyone is on the same page.

###4: Iterative Development

In this stage, we apply the agile methodology of iterative development by conducting time-boxed sprints.

Each sprint will implement a list of features, and produce a product increment that can be reviewed by the customer. It is important to understand that in iterative development we always pick the most valuable features to implement first.

The spirit of the this methodology is to establish a cadence of development where flexibility is embraced but expectance also needs to be met.

The SME is expected to work closely with designer and developer throughout the iterations and they better have responsive and context rich communication platform setup, such as Slack.

The output after each sprint is a new product increment. The dev team will demo it in a review meeting and then determine the next steps.

###5: Hardening and Deployment

After sufficient amount of iterations, hopefully the most valuable features are developed and the product is ready to be finalized.

Hardening is another term borrowed from software development. It refers to a concentrated effort to consolidate, to clean up the loose ends, to resolve conflicts, to pay the technical debts and to perform systematic inspection.

The word hardening literally means we are moving from the soft sides of things to the hard, immovable side. This could mean for instance, if you need voice over talent, this is the time to send the script as it is no longer subject to change.

Deployment means sending the product to where it will actually live and debug any issue that might appear.

Output: Final Deliverables in the form of published course outputs that have LMS wrappers, or source code of the project.

Estimating Cost & Effort

Elearning development is a costly endeavor. Exactly how costly? That will depend on multiple factors: the readiness of assets, the structure of the content, the level of interactivity required, and any specific assessment and deployment specifications.

An easy way to gauge the effort & cost of your elearning project is to think of it in relation/proportion to classroom teaching. This is especially handy if you already have a classroom session for the particular project.

According to Chapman Alliance (an elearning research entity), a level 1 elearning project (defined as having the most basic kind of interactivity, almost like an automated Powerpoint) would require from 49 to 125 hours for one hour of classroom content.

If the interactivity level increases, needless to say the cost will significantly increase. For level 2 elearning projects, the average ratio would be 184. Level 2 is the kind of elearning program that combines page turner type of content with some learner interactions such as drag and drop, tabbed interactions, timelines, etc. There might also be a limited amount of branching. This level would be considered typical of most elearning produced today.

Level 3 is defined as programs that incorporate significant amounts of branching, gamification, animations, and/or customizations for a unique end-product.

There is also understood that extensive video production and coding may be involved.

For this level of effort, the average time to produce one hour of classroom content is 490 hours.

While I feel this scale is accurately reflecting the rapidly rising ratio in terms of complexity, my level system is a little different. It contains five levels and the ratio (always estimations) come from the projects that I have worked on in the past.

Level 1: Rapid development

If your course involves mostly existing texts and images/videos and there is little interactivity requested (a few quizzes are okay), you can consider Articulate Rise, which can be very speedily developed and deployed. It also gives you the benefit of mobile responsiveness.

Cost Ratio: 50

Level 2: Converting ILT

If your course is basically a straightforward duplication of classroom lecture (no hands-on), then most likely you have a Powerpoint file ready to use.

In this case, the work consists of adding voice over narration and certain amount of interactive elements to make it self-paced.

Cost Ratio: 100

Level 3: Custom design from scratch

If your training doesn’t already have a Powerpoint to begin with, here is the good news: you get to design everything from scratch!

The custom design involves a deliberate rethinking of the structure of learning (can be no longer linear) and strategies for assessment.

At this level, some power tools such as screencast, animated videos are included the finished product exhibits medium level of interactivity.

Cost ratio: 200

Level 4: Engagement requested

There are times when your training has all the above but still feel insufficient. What is lacking is the engagement. There are many different ways to boost engagement, and we will discuss some of the strategies in chapter 4.

Engagement is definitely a designer feature and goes beyond the ready to use templates of things. Consequently, any effort in this direction will be significantly more costly .

Cost ratio: 200-400

Level 5: No expense spared!

If you have unlimited resources that allow you to design a truly innovative experience and produce all the assets you need and program all the interactive mechanism (plenty of triggers and variables), only sky is the limit!

Cost ratio: over 500