The Fork in the Road: Claude Code vs CoWork

Technical architecture comparison: Local execution model vs cloud infrastructure

Technical architecture comparison: Local execution model vs cloud infrastructureMany years from now, when agents run our lives autonomously, we may look back at January 12, 2025, as the fork in the road—the moment Anthropic launched CoWork and set two visions of AI assistance on divergent paths.

On the surface, CoWork appeared unremarkable. For the past year, we have heard a lot about Claude Code, that terminal-based agent developers had been using to refactor codebases and debug errors autonomously. But Anthropic had noticed something unexpected: users were hacking Claude Code for decidedly non-coding work. Sorting vacation photos. Renaming thousands of files. Organizing research notes.

CoWork was that behavior, productized. A quick pivot of a hugely successful thing.

The speed of development tells its own story. Four engineers built CoWork in roughly ten days, using Claude Code itself to generate most of the code. “It was pretty much all Claude Code,” Boris Cherny would later say. The child building itself from the parent’s blueprints—we’ve seen this pattern before, but never quite like this.

CoWork shares DNA with Claude Code, yet profound differences lie beneath the surface. Right now they coexist as three tabs in the Claude Desktop app: Chat, CoWork, Code. A triptych of possibilities. But this proximity masks a deeper architectural divergence.

Claude Code runs on your machine. CoWork provisions a VM and gives the agent its own computer. This might seem like a pragmatic choice—serving non-developers, enabling generic productivity work. But here’s what makes it fascinating: this single architectural decision profoundly shapes what each system can ultimately become.

The question isn’t just about implementation. If they share a foundation, what decision point created such different trajectories? Why did CoWork choose to own the execution environment when Claude Code’s approach already worked? And what downstream consequences flow from that choice—not merely in cost or performance, but in the fundamental relationship between user and agent?

This essay explores how two products born from the same codebase diverge in ways that go far beyond surface differences, and what their architectures reveal about the future of AI assistance itself.

Development History Sources:

- CoWork built in 10 days by four engineers

- Boris Cherny on CoWork’s rapid development with Claude Code

- Anthropic’s CoWork announcement

A Tale of Two Architectures

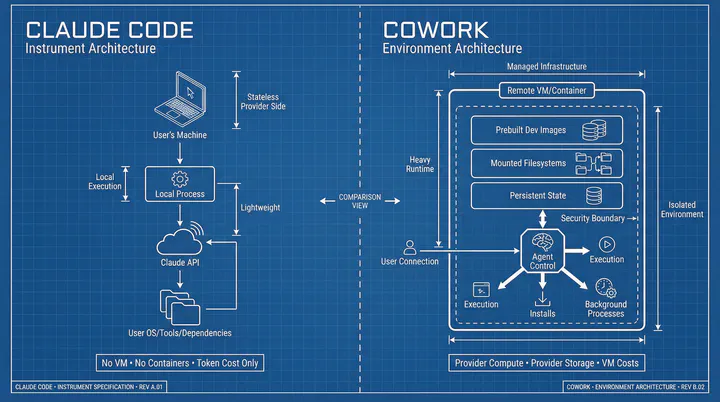

Claude Code represents a refreshingly minimalist design. At its core, it’s a CLI wrapper around Claude that delegates execution to your own machine. The key insight here is that Claude itself never owns the environment—it only reasons about it. Think of it as the brain that plans and directs, while your local machine does the actual heavy lifting.

Under the hood, Claude Code runs as a local process, talking to Claude’s API and leveraging your existing setup: filesystem reads and writes, shell execution, and diff-based edits. The environment is simply your OS, your tools, and your dependencies. There’s no VM, no container orchestration—just a local agent loop and an API connection.

This simplicity is the source of its speed. Multiple sessions are trivially cheap because state lives in files and conversation context, with isolation handled by your shell rather than infrastructure. Your compute power, your storage, your rules. The only vendor cost? Tokens. The design philosophy is elegantly simple: let the model reason, let the user’s machine do the work.

CoWork takes the opposite approach. It’s a managed execution environment with an agent on top, selling reproducibility, isolation, and persistence as features rather than nice-to-haves. Here, the agent isn’t just suggesting commands—it has full control over execution, installs, background processes, and long-running tasks.

This power demands infrastructure. Typically, you’re looking at a VM or container per workspace, complete with prebuilt dev images and mounted project filesystems. The VM isn’t optional overhead; it’s necessary to guarantee isolation between users, deterministic behavior, and proper security boundaries. The agent needs persistent state outside chat context for running services, caches, build artifacts, and its own memory.

Of course, this comes at a cost. Compute and storage are on the provider’s dime, idle time still burns money, and scaling becomes an infrastructure orchestration problem. The design philosophy here is fundamentally different: give the agent a computer of its own.

Instrument vs. Environment

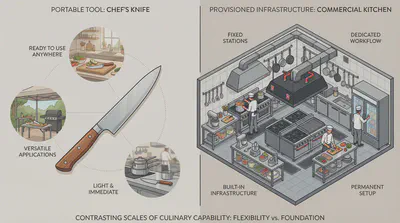

Here’s the heuristic that clarifies everything: Claude Code is an instrument. CoWork is an environment.

Think of it like the difference between a chef’s knife and a commercial kitchen. A professional chef carries their knife everywhere—it works in any kitchen, integrates seamlessly with whatever ingredients and workspace they find, and costs nothing beyond the initial purchase. The knife augments their skill but depends on the chef’s presence and direction. If something goes wrong, they can sharpen it, replace it, or work around it immediately.

A commercial kitchen, by contrast, is a provisioned space. You don’t bring it with you; you enter it. Everything is there—industrial ranges, refrigeration, ventilation, safety systems—managed infrastructure designed for consistent, reproducible results. Multiple chefs can work in parallel within its boundaries. But it’s expensive to maintain even when idle, you can’t easily spin up a second one, and if something breaks, you’re calling the landlord or facilities management.

An instrument augments your capabilities and integrates into your workflow. An environment replaces your setup with managed infrastructure. The distinction shapes not just cost and performance, but your entire mental model. Are you conducting an AI assistant through your existing setup, or are you provisioning workspace for an autonomous agent?

This architectural split creates ripple effects everywhere. Claude Code runs on your machine, starts instantly, and costs you nothing beyond API tokens. CoWork provisions a VM, takes time to spin up, and bills for infrastructure whether you’re actively working or not.

When something breaks in Claude Code, you’re in control—it’s your machine, your files, your fix. When CoWork’s environment has issues, you’re waiting for the provider to sort it out. This situation is similar to the artifact feature. The artifact you see can be viewed, and revised via further prompting, but not directly.

But these practical differences point to something deeper. The real question is: what can each system become? The architecture doesn’t just affect speed or cost—it determines three fundamental capabilities that shape the entire user experience.

Can you leave and come back later? (resumability) Can you connect it to your other tools? (attachability) Can it work without your constant supervision? (autonomy)

These three dimensions reveal why the fork matters. Let’s examine each one.

Resumability: The Illusion Versus the Reality

Start with resumability, because it exposes the core architectural difference most clearly.

The difference in how these two systems handle resumability reveals something deeper about their architectural philosophies. For Claude Code, resumability is mostly an illusion created by locality. A Claude Code session consists of just three things: conversation history stored with Claude’s service, files on your disk, and your terminal process. Only the first is owned by the provider—the rest lives entirely on your machine.

When you “resume” a Claude Code session, you’re not actually reviving an agent instance. You’re simply restarting a client and re-sending context. The world state—your repo, virtual environment, build artifacts, running services—never went away. This explains why multiple terminals work fine, why crashes are survivable, and why sessions feel persistent even when the agent itself is not. From an implementation standpoint, Claude Code is stateless on the provider side and stateful on your machine.

In CoWork, resumability is literal, not metaphorical. A session includes a live VM or container, a running agent process, possibly background services, a mounted filesystem, and in-memory agent state. When CoWork says “the app must remain open,” that’s a real constraint. The desktop app appears to function as a control plane client (coordinating the remote runtime), a keep-alive channel (signaling the session is still active), and potentially a secure tunnel. Closing it may suspend the VM, discard agent memory, or sever execution authority.

Whether you can resume depends on whether the VM is paused versus destroyed, whether agent memory is checkpointed, and how long the provider retains idle resources. This explains why you typically get one active session and why resuming feels fragile.1

The economics reinforce these constraints. Claude Code must preserve only conversation transcripts (cheap) and files you already own (free to provider). CoWork must preserve VMs, disk snapshots, RAM state, and network bindings—infrastructure costs that scale very differently. If CoWork allowed unlimited resumability, multiple parallel sessions, and long idle times, the economics would collapse. Agent memory is in-process: kill the process and memory is gone. The VM lifecycle appears tied to the UI lifecycle—the desktop app functions as the lease holder, so closing it likely expires the lease. And concurrency explodes cost: one user with one VM is already expensive; one user with many VMs is not viable at scale.

So CoWork is resumable in the narrow sense of “you may reconnect to a paused workspace under controlled conditions,” not “this agent will always be waiting.”

The difference is fundamental: Claude Code’s session is reconstructible from files and history. CoWork’s session is existential—lose it and you lose running state that cannot be recreated. Claude Code is resumable because it never really owned anything. CoWork is fragile because it owns everything. That fragility is not accidental—it’s the cost of giving the agent a real machine.

Claude Code Architecture:

- Claude Code conversation history storage

- Session persistence and management

- Multi-terminal coordination

- How Claude Code works

CoWork Architecture:

- CoWork VM architecture deep dive

- CoWork security architecture

- Getting started with CoWork

- CoWork guide 2026

Attachability: We Do Not Reinvent the Wheel

The second critical capability reveals an even sharper divergence: how—or whether—you can integrate these agents into your existing tools.

A common pattern has emerged around Claude Code: people don’t “integrate the model” into their applications. Instead, they integrate a thin layer that selects context from the tool, sets an appropriate working directory, and exposes a few core actions—read, write, search, run—through the Claude Code CLI. The practical reason this works is architectural. Claude Code plugins are explicitly designed as lightweight bundles of extension points: slash commands, agents and subagents, hooks, and MCP servers that install with a single command rather than requiring a heavy runtime.

This has enabled integration across very different domains. For coding, back when Cursor was still the go-to name for vibe coding, Claude Code was made available as a VS Code extension. This move let developers stay in their comfortable IDE—whether Cursor or vanilla VS Code—and access Claude Code’s agentic capabilities without switching contexts. For writing, multiple independent Obsidian plugins have emerged that essentially turn a vault into Claude Code’s project root. Claudian, for example, embeds full Claude Code agent behavior inside Obsidian: the vault becomes Claude’s working directory, with complete file read/write access, search, and bash execution, plus UX conveniences like attaching the focused note, @-mentioning files, and excluding notes by tag.

Why does this pattern generalize so easily? Because it works for any tool that operates on a collection of files. That collection can manifest in two ways. File-backed systems—Markdown folders, local documentation, code repositories—are the easiest case. You simply set the working directory to the project or vault and pipe file selections into the agent. Document-backed systems with APIs—Notion, Google Docs, Confluence—are slightly more complex due to latency and limited scope. You use MCP to expose “read doc / write doc / search” as tools, and Claude Code can invoke them through the same plugin bundle model.

Obsidian illustrates why this works so well. It’s just an Electron app with a plugin API and a file-backed workspace. The file-backed nature enables local access, which means efficiency. By contrast, MCP over network calls is currently much less efficient—usable, but noticeably slower for interactive work.

The general pattern for attaching Claude Code to any application follows three steps: define context capture for the tool (current document, selection, related files), define the action surface (write back to document, create note, search), and package it as either an embedded Claude Code session or an MCP server plus Claude Code plugin bundle.

CoWork cannot replicate this. The VM architecture that gives CoWork its isolation and persistence also creates an integration barrier. Your existing tools live on your machine. CoWork’s agent lives in a remote container. There’s no straightforward way to make your local Obsidian vault or VS Code workspace the agent’s working directory. You can’t pipe context from your local filesystem into a remote VM without building complex tunneling infrastructure.

You could theoretically build integrations through web APIs—have your local tool upload context to CoWork’s environment, get results back, sync changes. But this destroys the simplicity that makes Claude Code integrations trivial. Now you need bidirectional sync, conflict resolution, network error handling, and authentication. The lightweight plugin becomes a heavyweight integration project.

The result is that CoWork remains isolated. It’s an environment you enter, not an instrument you embed. This isn’t a missing feature—it’s a necessary consequence of the architecture. Environments must be self-contained. Instruments can be composed.

Autonomy: Tool Versus Agent

The third critical capability—autonomy—reveals the clearest divergence in what these systems are becoming.

The viral emergence of OpenClaw, Moltbot, and Clawdbot reveals a pattern people want: stateful agents that run continuously as background services, accessible via messaging apps. You close your laptop, and the agent keeps working. You delegate a task in the morning and return to completed work in the evening. These agents maintain persistent state across sessions, operate asynchronously, and initiate actions proactively—sending reminders, monitoring email, checking flight statuses.

This isn’t necessarily “true autonomy”—we don’t yet know what that looks like. But it’s a kind of autonomy that didn’t exist in mainstream products before, even though it was always technically feasible. The interesting question is why it emerged from the community rather than from Claude Code or CoWork, and what that tells us about architectural fit.

Neither Claude Code nor CoWork delivers this pattern today. But their architectures point to very different futures.

Because Claude Code was the only game in town in 2025, the community built autonomy through sheer determination. Background tasks let dev servers and builds run without blocking workflow. The ralph-wiggum plugin implements stop-hooks that let Claude work through task lists for hours. Scheduler plugins trigger overnight refactorings: “every night at 2am, update deprecated APIs.”

These are impressive engineering achievements. They’re also fighting the architecture.

Claude Code is stateless on the provider side. Your terminal must stay open—close it and the session ends. There’s no persistent agent state across sessions. When you “resume,” you’re reconstructing context, not reviving a persistent agent. The scheduler can trigger at 2am, but only if your terminal is still running. This isn’t a missing feature—it’s the cost of the architectural choice. Claude Code never owns the environment. That’s its strength for integration and flexibility. But it means the agent can’t persist independently.

When users build autonomous personal assistants like OpenClaw and Moltbot—self-hosted background services with persistent memory, accessible via messaging—they’re recreating what CoWork’s architecture already provides.

CoWork provisions a live VM with agent memory, running services, and filesystem state. The sandboxed runtime with hard security boundaries means you can delegate “organize 10,000 photos” and trust it won’t rm -rf / your system. CoWork naturally handles bounded autonomous tasks: file organization, PDF-to-spreadsheet extraction, research synthesis. Its mental model is already “describe outcome, agent executes until complete.”

The missing pieces are architecturally straightforward: background running (desktop app can close), session persistence across days, cost model for long-running VMs. These aren’t architectural pivots—they’re constraint relaxations.

The Agent Teams Paradox

Here’s where the architectural mismatch becomes most apparent: Agent Teams.

CoWork currently uses subagents—a hierarchical model where the lead spawns temporary workers for specific subtasks. They report results and terminate. Claude Code recently introduced Agent Teams (experimental as of February 5)—a shift to collaborative networks. Multiple full-fledged Claude instances work as teammates, not subordinates. They share a centralized task list, message each other via a local mailbox system (~/.claude/teams/), and self-coordinate: when one finishes a task, it consults the shared list and claims the next item.

This is the infrastructure for hours-long autonomous work. Agents coordinate without human intervention, unblock each other, and systematically work through complex multi-step projects.

The paradox: Agent Teams should be in CoWork, not Claude Code.

CoWork’s architecture—managed VM, persistent state, security boundaries—is precisely where multi-agent coordination makes sense. Long-running autonomous tasks benefit from agents that delegate to peers and self-organize work. The VM could safely contain multiple agent processes in parallel without requiring the user to manage terminal sessions or worry about blast radius.

Instead, Agent Teams shipped in Claude Code, where the architecture fights it. Multiple terminals, shared state on your local filesystem, stateless sessions that reconstruct on resume. It works, but it’s swimming upstream.

Meanwhile, CoWork—the system architecturally designed for sustained delegation—still uses temporary subagents.

This isn’t a criticism of shipping strategy. Claude Code is the frontier product, and Agent Teams are experimental. But the mismatch reveals something deeper: the features are migrating toward the architectural fit they need. Imagine CoWork with Agent Teams, freed from the “desktop app must stay open” constraint. You give it a task at night: “Research this topic, extract data from these documents, generate a presentation.” A team of agents coordinates autonomously for hours, presents results in the morning.

That’s the vision CoWork’s architecture enables. Not because it has those features today, but because removing constraints (background running, cross-day persistence) is straightforward when the foundation—persistent VM, agent state, safe isolation—already exists.

Claude Code can build autonomy features, and it will. But it’s building them on an architecture optimized for interactive, human-in-the-loop work. CoWork is one relaxed constraint away from being what OpenClaw and Moltbot demonstrate people want: a personal agent that runs independently, holds context persistently, and operates safely without constant supervision.

The architectures dictate the destinations, regardless of which features ship where.

Further Reading on Autonomy:

Autonomous Agent Patterns:

- What is OpenClaw: Open-Source AI Agent

- Everything About Viral Personal AI Assistant Moltbot

- Clawdbot GitHub Repository

- Stateful Agents: The Missing Link in LLM Intelligence

Claude Code Autonomy Features:

- Background Tasks Announcement

- ralph-wiggum Plugin for Autonomous Loops

- Claude Code Scheduler

- Agent Teams and Task Coordination

CoWork Capabilities:

Two Paths Forward

We’re watching a historical divergence that matters. Two products born from the same codebase, splitting along architectural lines that will determine what AI assistance becomes over the next decade.

Claude Code will probably evolve into an increasingly sophisticated instrument—something you conduct rather than delegate to. Expect deeper IDE integrations, more powerful context management, richer plugin ecosystems. The terminal will become a command center where you orchestrate AI capabilities across your entire development workflow. It will remain fast, flexible, and powerful precisely because it never tries to own your environment. You’ll trust it with your codebase because you can see everything it does, interrupt it anytime, and maintain full control.

CoWork, on the other hand, has the opportunity to evolve toward autonomous operation—not as a tool you use, but as an environment you provision. The “desktop app must stay open” constraint will be gone. Sessions will persist across days. Background running will become standard. Agent Teams will migrate from Claude Code’s local coordination to CoWork’s managed runtime, enabling true multi-agent workflows that run unattended for hours. Eventually, it may split off entirely—a personal agent accessible via messaging, running on infrastructure you don’t think about, working on tasks while you sleep.

Tokens will be burnt in billions.

These architectural details about CoWork’s session management and resource policies are inferred from documented behavior and independent reverse-engineering efforts. Anthropic has not published detailed implementation specifications for CoWork’s VM lifecycle management. ↩︎