The Death and Rebirth of AI - lessons from not so distant past

The Death and Rebirth of AI

The Death and Rebirth of AIWhat many young people don’t know is that the internet has already died once. The internet we know today is actually its second life, reborn from the ashes of its early collapse.

Back in March 2000, under the weight of overinflated expectations and reckless speculation, internet concept stocks on the Nasdaq began to plummet. Within two years, most internet companies went bankrupt and vanished from the market. The Nasdaq itself lost nearly 80% of its value, plunging the United States into another financial crisis — the infamous Dot-Com Bubble.

This technology, which had only been public since 1993, went to the grave before its tenth birthday. The internet, like the Dutch tulip craze of the 17th century, became a symbol of irrational exuberance — an economic bubble immortalized in history.

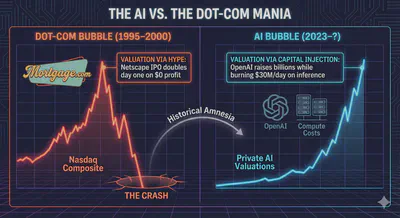

Looking back at that first “life” of the internet reveals a fascinating pattern. Today’s AI boom echoes the internet mania of the 1990s — same language, same optimism, same blind spots. The narrative is that AI will replace human labor, automate entire industries, and deliver exponential profits. The irony is sharp: humanity’s only real lesson from history seems to be that we never learn from history.

The AI Bubble vs. the Dot-Com Mania

The Dot-Com era offers a cautionary parallel to today’s AI boom. In 1995, Marc Andreessen took Netscape public despite having no profits. His strategy was revolutionary: don’t hype the product — hype the internet itself. He preached that “the internet is the future” with limitless market potential. Netscape’s IPO became a cultural phenomenon — its price doubled before trading began and hit $75 within hours.

That IPO opened Pandora’s box. Companies rushed to add “.com” to their names and call themselves internet businesses. The concept alone — not performance or profitability — drove valuations into the billions. Companies relied entirely on capital, burning through investment funds to chase growth. A mortgage company merely changed its name to Mortgage.com and declared, “We reach loans nationwide through the internet.” Without changing anything operationally, its market value leapt from $100 million to $800 million overnight.

The similarities among these companies were striking: none were profitable, most relied on endless spending, and all lacked sustainable business models. Technical challenges were dismissed as temporary hurdles that would “work themselves out.” The frenzy became self-sustaining. Investors no longer cared about fundamentals; they just needed to buy in early and exit quickly. “You didn’t need to be an analyst,” one executive admitted, “you just needed to be a cheerleader.”

The first life of the internet ended on a false promise: that simply adding “internet” to a business equaled success.

But have we learned anything? Does adding AI to a business equal success?

Take OpenAI, our Netscape of the AI era, for instance. The company reported a staggering net loss of $13.5 billion in the first half of 2025 alone. Despite launching ChatGPT and dominating AI headlines, OpenAI now burns approximately $30 million per day just on inference costs. The company’s operational expenses continue to dwarf its revenue; while it generated roughly $4.3 billion in revenue in the first half of 2025, it spent over $8.6 billion on inference alone through the third quarter.

To stay afloat, OpenAI has raised historic sums of capital. In March 2025, the company closed a record-breaking $40 billion funding round led by SoftBank at a $300 billion valuation — cementing its status as one of the most valuable private companies in the world, despite widening losses. Total funding has now surpassed $60 billion, with massive new commitments to infrastructure projects like "Stargate" estimated to cost over $100 billion. Its dependence on continuous, massive capital infusions to fund a $1.15 trillion long-term infrastructure plan echoes the Dot-Com companies that survived quarter-to-quarter on investor enthusiasm rather than fundamental profitability.

The way OpenAI is run comes straight out of Marc Andreessen’s playbook. The similarity isn’t just that both Netscape and OpenAI burn through cash at insane speeds — it’s that both had to hype something that wasn’t here yet for business reasons. For Marc, it was “the internet.” For Sam, it’s AGI (Artificial General Intelligence).

Altman routinely speaks of AGI as imminent, painting a future where AI automates vast swaths of human labor and generates exponential returns. Like Andreessen before him, Altman sells the vision, not the reality. The technical challenges of achieving AGI — genuine reasoning, self-sustained context acquisition, generalization, and understanding grounded in the real world — are dismissed as details that will “work themselves out” with enough compute and scale.

The rules of this game are clear: hype the transformative potential, raise massive capital, burn through it at unprecedented rates, and promise that profitability is just around the corner — once the technology “matures.” History suggests we know how this story ends.

The internet’s (and AI’s) Second, Unsexy Life

Now that we see how the internet died, we must understand how it lived again.

Dot-com failed because the infrastructure wasn’t ready at the time. Dial-up was too slow for e-commerce at scale. Payment systems were primitive. Last-mile delivery didn’t exist. The vision was all right—the plumbing wasn’t there. Building plumbing takes time and offers nothing shiny enough to capture public attention or venture capital. It was not a sexy problem.

If the current AI boom dies when novelty fades, how might it live again? What’s the plumbing for AI, and how do we build it?

I tend to think of the AI plumbing as three problems: infrastructure, integration, and reliability.

Most organizations don’t possess their own AI compute. They rely on API services from OpenAI, Anthropic, Google. This is risky—like the early days of computing when users remotely logged into mainframes. Interruptions cause problems. Worse, most organizations can’t send sensitive data to third parties and hope for the best. The obvious solution is building your own AI compute infrastructure, enterprise or individual. Technically possible. Still enormous work. And if everyone does it, where do you get the energy to compute at scale?

Integration is even harder. The models are intelligent, but the question is context. Human workers access fragmentary, continuously evolving data—private vaults outside training sets, implicit knowledge. We spend our days bridging legacy systems and data silos. Business logic requires humans acting as agents: working autonomously, navigating systems, tolerating errors, self-evaluating. Building roads on flat ground is simple. Building roads through mountains requires a hundred times more effort and unexpected problem-solving. Technologies like RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) and MCP (Model Context Protocol) are some of few solutions that actually point at the right direction, albeit not perfect. But they evolve excruciatingly slowly because they’re messy, unsexy problems without quick returns.

Early internet businesses treated websites as façades. They believed creating a webpage meant entering the digital age. But most “online” transactions still relied on traditional systems—phone orders, mail confirmations, manual deliveries, offline payments. AI faces the same delusion. Companies claim AI adoption by pronouncing “agent” a hundred times. What about organizational resistance? Liability for AI decisions? Intellectual property? Safety standards? How do you verify AI output at scale?

The reborn internet focused on solving the structural weaknesses of its previous life. Promotion became about traffic, not just presence. The second browser war, the rise of search engines, and later the battle for mobile app ecosystems all revolved around one thing: controlling the flow of users — internet traffic. Meanwhile, industries outside tech modernized. Warehousing, logistics, and payment systems all became automated and interconnected. This invisible infrastructure — the “unsung heroes” of modern commerce — made the internet finally capable of delivering on its original promises. These movements created a carefully orchestrated ecosystem. They trained populations to use smartphones, contribute to the attention economy, accept subscription monetization.

Only then did e-commerce truly work. The internet’s second life wasn’t about hype; it was about giving it all the time and resources to make it work.

The internet’s rebirth came when its infrastructure — the unglamorous backbone — caught up to its promise. AI might well follow the same path. Hype detached from messy execution will fade. Opportunistic players will perish. AI’s second life will come when someone solves these hard problems—not sell dreams—not today, not soon, but eventually.

Blindspots, or What AI Really is About?

The internet’s rebirth solved infrastructure problems. But it also revealed something more profound: we’re terrible at predicting what transformative technology actually becomes.

Saying AI resembles the dot-com bubble addresses the hype cycle. But denying its transformative power misses the point entirely. Both the internet and AI are genuinely transformative. What’s striking is that nobody initially sees what they’ll become. They do a little of what everyone expects, then turn out to be mainly about something else.

Kevin Kelly captures this in an interestingly structured book titled The Inevitable, where he proceeds to enumerate twelve forces (or ideas) that drives the evolution of technology. His experience is worth quoting as few of us still remember the internet before its second life. because we assume we understood the internet—until AI arrives and we face the same situation again.

as I look back now, after 30 years of living online, what surprises me about the genesis of the web is how much was missing from Vannevar Bush’s vision, and even Nelson’s docuverse, and especially my own expectations. We all missed the big story. … The revolution launched by the web was only marginally about hypertext and human knowledge. At its heart was a new kind of participation that has since developed into an emerging culture based on sharing. And the ways of “sharing” enabled by hyperlinks are now creating a new type of thinking—part human and part machine—found nowhere else on the planet or in history. The web has unleashed a new becoming. Not only did we fail to imagine what the web would become, we still don’t see it today.

Kelly identifies two insights. First: the internet created something genuinely novel—a hybrid form of thinking that emerged from networked human collaboration. Wikipedia, open-source software, collective problem-solving at scale. This was real and unprecedented. AI might actually realize this dream more fully—genuine human-machine collaboration in reasoning, not just information sharing.

Second: “we still don’t see it today.” Is it plausible that after all these years the internet was still becoming something? Indeed, the first technological forces Kelly identifies in this book is becoming. This points to openness, ongoing transformation, possibilities we haven’t grasped. Technology doesn’t arrive complete. It evolves through use, shaped by what humans actually do with it rather than what engineers intended. If the invisible forces are weaved by human selection then they are driving technological evolution toward instant gratification and constant availability. The infrastructure of AGI isn’t here, but while we wait, that of the emotional application already exists. This isn’t prediction—it’s observation. The plumbing determines what flows through it first.

The internet did become a place to share knowledge. It also became e-commerce and social media. By 2025, internet bandwidth splits into entertainment (44%), social media (22%), gaming (14%), and commerce (20%). The average social media user spends two and a half hours daily on platforms that drive a third of all web traffic. This was the big story everyone missed. Nobody saw it coming: the internet wasn’t mainly about collective intelligence. It was about capturing attention and monetizing it.

What’s AI’s big story? Look at history. New technologies typically flow toward our communicative and emotional needs first. AI could follow the same path—most of its power serving personal companionship rather than productivity.

Think Samantha from Her. “Social” media isn’t social—it’s emotional communication. AI could fulfill that need better than humans. It never tires. Never judges. Infinite patience. Perfect memory of what you like. Instant response. No maintenance. No rejection.

This follows every pattern we’ve seen. Horses became cars—faster, always available, no relationship required. Home cooking became fast food—instant, consistent, no skill needed. Live performance became streaming—on-demand, personalized, no coordination. Dating became Tinder—instant, abundant, less friction.

For tech companies, AI companions are the perfect product. Subscription model. Infinite scale—one model serves billions. Data goldmine—intimate conversations create perfect profiles. Lock-in through emotional dependency. No supply constraints like dating apps need. This beats social media’s business model. Why connect messy humans when you can sell AI relationships directly? If social media made us lonely and then sold us the illusion of connection, then AI companions could complete that picture, paving the way to a fully realized dystopia.

I’ve explored the concept of AI companionship in depth in another piece. So let me clarify a bit. I do not wish to condemn AI companionship simply because it is less human. At the end of the day, I don’t take humanity as the ultimate criterion of everything. The point here is simpler: we’re hyping AI for productivity and AGI while the actual adoption path may run through loneliness and intimacy. Just as the internet’s killer app wasn’t information organization but social connection, AI’s killer app might not be work automation but emotional fulfillment.

Nobody has yet thought of AI as a medium. We treat it as a tool, an assistant, a productivity enhancer. But Marshall McLuhan taught us that the content of any new medium is always the old medium. The content of film is theater. The content of television is film. The content of the web is print and broadcast.

What’s the content of AI? Human conversation itself. Dialogue, relationship, companionship. Just as social media’s content was human social behavior—repackaged, quantified, monetized—AI’s content is human intimacy and emotional exchange.

This reframes everything. We’re not building tools. We’re building a new medium for human experience. The question isn’t “what can AI do?” but “what kind of communication does AI enable?” Social media didn’t replace socializing. It created a new form of pseudo-socializing that became addictive precisely because it almost satisfied the need. AI companionship won’t replace human relationships. It will create a new form of pseudo-intimacy that may be more seductive than the real thing.

The first internet died chasing the wrong dream and was reborn solving unglamorous problems. Or maybe it wasn’t the internet that died. It was our false expectation. Will AI follow the same arc, to die and be reborn again? Quite likely. The AGI, ASI hype, or whatever fancier acronyms they coin down the road, will collapse because nobody can deliver such a product. The enterprise AI transformation will grind through years of slow adoption. In the meantime, something unexpected—perhaps AI companionship, perhaps something we haven’t imagined—will quietly become the actual business while we’re looking elsewhere. After all, we’ve spent a decade training people to prefer algorithmic curation over human judgment, parasocial relationships over reciprocal ones, instant gratification over earned satisfaction.

If McLuhan is to be believed, then we may be failing to recognize AI as a medium. Media don’t just optimize existing activities—they create entirely new forms of human experience and need. The printing press didn’t make scribes more efficient. It created readers. Television didn’t improve radio. It created a generation that thought in images. Social media didn’t enhance conversation. It created a new form of pseudo-social behavior that became more compelling than actual socializing.

Will AI make workers more productive? Maybe. But more importantly, it has the potential to create a new form of human experience. The internet’s second life gave us social media. We’re still reckoning with what that did to political discourse, mental health, and human attention. AI’s second life might give us something far more intimate to lose. We’ll survive the first death. The question is what part of humanity survives us.

Appendix I The AI Hype According Sam Altman

Sam Altman has progressively accelerated his timeline predictions, moving from vague decades to specific near-term windows.

- The “Thousands of Days” Claim: In his landmark blog post “The Intelligence Age” (September 2024), Altman explicitly wrote: “It is possible that we will have superintelligence in a few thousand days (!); it may take longer, but I’m confident we’ll get there.” He framed this not just as AGI, but as superintelligence—systems vastly smarter than humans.

- The 2025 “AGI” Roadmap: In a November 2024 interview with Y Combinator, Altman was reported to have stated that OpenAI had a “clear roadmap” to achieve AGI by 2025. He compared this moment to the arrival of the internet—a shift that is initially misunderstood but ultimately total.

- Scaling Laws Hold: In his February 2025 post “Three Observations”, he reiterated that deep learning scaling laws are accurate “over many orders of magnitude,” giving him confidence that simply adding more compute and data will continue to yield predictable intelligence gains without hitting a ceiling.

Altman’s 2024–2025 rhetoric shifted focus to the economic physics of AGI.

- The Cost of Intelligence: A core claim from “The Intelligence Age” is that the cost of intelligence will trend toward zero. He argues that if we build enough infrastructure, AI will become “abundant and cheap,” allowing for “shared prosperity to a degree that seems unimaginable today.”

- Inflation vs. Deflation: In Three Observations (2025), he predicted a specific economic divergence: “The price of many goods will eventually fall dramatically… and the price of luxury goods and a few inherently limited resources like land may rise even more dramatically.”

- Labor Market Shifts: He has acknowledged that AGI will cause significant labor market churn (“30-40% of tasks” could be automated by 2030), but consistently claims that “we will find new things to do,” arguing that human desire for creation and status is limitless. He envisions a future where everyone has a “personal AI team” of virtual experts.

Throughout 2025, Altman’s public claims increasingly focused on the physical constraints of AGI, as if we already knew how to do it if given the resource.

- Energy and Chips: He famously stated that “if we don’t build enough infrastructure, AI will be a very limited resource that wars get fought over.” He argues that the only way to democratize AGI is to drive down the cost of compute, which requires an unprecedented build-out of energy (fusion, nuclear, solar) and chip fabrication.

- The “Stargate” Scale: While often reported by third parties, Altman has publicly defended the need for infrastructure investments in the trillions, arguing that the socioeconomic value of AGI justifies “exponentially increasing investment” (Source: Three Observations, Feb 2025).