Walden - 瓦尔登湖

Walden is a name that needs no introduction.

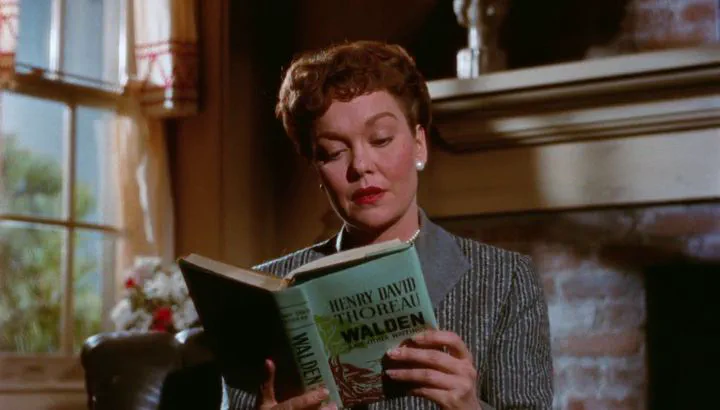

It’s a curious thing, seeing a book like Walden, a work so often associated with a certain… intellectual elevation, pop up in unexpected places. Like in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows, where Cary reads from a copy of Walden, belonging to the younger man she’s fallen for.

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it’s because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”

Honestly, seeing Thoreau referenced in a classic tearjerker felt almost… wrong. It clashed with my own, deeply personal relationship with the book. It felt a bit like a fishmonger using pages ripped from Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation to wrap his daily catch.

But perhaps the misunderstanding is entirely my own. We all cling to certain beliefs in our youth, don’t we? Ideas about patriotism, social justice, revolutionary movements, spirituality, even the “ideal” partner.

Years ago, when I translated Walden, living in my own secluded cabin beside a metaphorical pond, I pictured Walden as a haven of solitude, a place of vast, untouched nature. Imagine my surprise, then, when I finally visited Concord in 2004. Not only did the tiny replica of Thoreau’s hut, complete with a statue out front, seem almost comical, but Concord itself was bustling with people and cars, and Walden Pond… well, it had become a popular public swimming spot. It wasn’t quite the serene escape I’d envisioned.

In a blog post published in 2/19/2008 I wrote:

A recent reading of Stanley Cavell’s The Senses of Walden brings back to me all those delightful yet painstaking days of translating Thoreau. But after the initial nostalgia phases out, what is left in front of me is nothing but an interpretation that I find unfortunately incompatible with mine. As a translator, I have to go through the words one by one and make perfect sense of them, and often in a deeper level than they literally say. And these small pieces of making senses ultimately add up to what Schleiermacher calls the “inner trajectory”. Or should I say, using Gadamer’s terminology, the process of translating a text fuses my own horizon with the horizon of Walden. It is on this base I claim, for I do, and sincerely, that I understand this book.

For someone like Cavell, this intentionality is still acknowledged. Yet obviously (for anyone familiar with Cavell), it is not this very intentionality he is transcribing or even addressing. It serves as a mere departure point, from which Cavell will produce his own writing. The task of those seminars from which the book originates is not to tell people what Thoreau means, for they can just read the book and find out by themselves, but to tell, what does he (Cavell) make of Walden. It is the “senses of Walden”, not “making senses of Walden”.

Translating is very different. In translating the performative options are limited. And when I perform, I feel guilty unless I am absolutely certain. This, of course, does not apply to all kinds of translations. The difficulty of any particular translation can be simply determined by this: try to feed the text to a machine (a translation software) and see how much you can gather from the result—how readable is the result? For a case like Thoreau, I think it would be less than five percent.

Translating a text such as Walden is totally a sacrifice. Come to think of it, I have problem understanding why I did it. It would be infinitely better if I had done something similar to what Cavell did, even if as a result, I can claim I understand the book better. Interestingly, when Thoreau claims that we should read those “heroic” or ancient books, he does not mean that we should try to understand them—we may not understand the nature of a certain light beam that is shed upon us, but it is still a glory to comprehend the consequences of being illuminated by this beam of light.

Putting in countless hours on this work over twenty years ago (maybe around 2001?), I wasn’t writing for a commission or even dreaming of publication. The joy, for me, was truly in the work itself. Finishing the book felt like closing one chapter and eagerly turning the page to a new one, as we often do in life.

And, in a wonderful turn of events, my translation was eventually published in 2009 by Yilin Press!

Enjoy reading the book and feel free to download a copy below.