Everything you want to know about film studies...

Who Should Read This?

There’s certainly no shortage of writing about films on the internet and beyond, but I hope what you’ll discover here is a refreshing take. Welcome to a series of articles designed as a self-paced course! Together, they provide an engaging introduction to the fundamental concepts of film aesthetics, a topic often explored in higher education across the US under the title Film Intro. In fact, these articles are drawn from my own lecture notes from teaching the course multiple times.

This series is crafted for anyone eager to gain a liberal education in the world of film. But I’ve also aimed to offer something unique—insights that you won’t find anywhere else. These articles blend film scholarship with pathways for further exploration. You’ll find this web course particularly appealing if you:

- Are curious about films but often find film reviews lacking

- Want to explore films beyond what’s playing at your local AMC

- Wish to learn how to discuss and write about films in a more meaningful way

And don’t hesitate to dive in if you:

- Struggle to pinpoint what we should study about films

- Have a low tolerance for films you don’t enjoy

- Aren’t planning to write about films at all

I truly believe that gaining knowledge about films can transform your perspective.

In a college setting, this would serve as a gateway course. Once you complete it, you could venture into more “advanced” topics like film history or specific genres, such as “East Asian Martial Arts Films.” But let me be clear: this isn’t the easiest subject in film studies. It delves into the most fundamental questions about film as an artistic medium—questions that will linger with you, as there are no definitive answers.

It’s important to note that an introductory film course can be approached in various ways. Some emphasize scriptwriting and Hollywood history, while others focus on economic, social, ethnic, and gender-related issues. All of these aspects are significant, but I believe it’s essential to establish a solid foundational understanding of film as an aesthetic experience. Therefore, the questions I concentrate on in my course include:

- What is the nature of our experience in cinema?

- What constitutes a film? What are its components? How do these elements interact?

- How do we study films? How do we analyze and interpret them?

By engaging with these posts, watching the accompanying clips, and participating in complementary activities (like analyzing and interpreting films), you’ll achieve a similar, if not identical, experience to that of taking a traditional film intro class.

Speaking of classes, if you’re in need of a textbook, I highly recommend David Bordwell & Kristin Thompson’s Film Art: An Introduction. This book is penned by leading scholars who bring not only a wealth of knowledge but also a genuine passion for the subject. First published in 1979, the authors have spent over 30 years revising and enriching the content to create its current form. Plus, the language is refreshingly accessible, unlike much of the film scholarship out there.

My lecture notes are designed to complement the book, and while they loosely correspond, there’s minimal overlap between the two. Enjoy the journey into the world of film!

What Is Film studies?

One of the most frequent reactions I got when I told people I study film is a blank expression, which reads to me, “what is there to study about films?” Some actually spit the said question out, sincerely looking for an answer. To answer this question I think it is useful to compare what film studies do to what film criticism does.

Film Criticism is a form of writing on film that everybody knows. It is basically a form of journalism. And it has all the traits of common journalism such as style, timely info, etc. It champions writing skill. It is essentially about how we feel about a film, about how does the film remind us about other films and stuff in life, about subjective evaluations, recommendations.

Academic film studies, on the other hand, is not about writing skill (although it still plays a part); it is rather about critical thinking and contribution to knowledge.

What is this knowledge?

Film is an aesthetic object. Film has its own artistic medium (although morphing). It is a unique audiovisual experience (not necessarily artistic) that rose to prominence in the 20th century. In fact, many would agree that film is one of the defining characteristic of the 20th century.

Although a film can be studied in aesthetic isolation, the general idea of film is decidedly a cultural phenomenon. In other words, most often than not, many individuals and institutions are involved in the production and consumption of film. This makes film an almost inevitable representation of cultural values.

It also has a history (or histories, like everything else). It makes use of a complex set of technologies. The process of commercial filmmaking is a highly organized economic activity. All these are complex phenomena that need to be carefully examined.

So how to Do We Study Films?

Imagine all the films in this world as an ocean. There are many ways to study this ocean.

- The science of ocean study is called oceanography.

- Every film is unique, but it also belongs to a broader context such as:

- Film School: basically a bunch of fishes/films that decide to swim together, for a while.

- National cinema: a particular corner, region of the sea that has its unique geographical shape, volume, amount of oxygen, food, sun light, etc. These correspond to the specifics of cultural milieu, industrial practice, period conception etc.

- A particular filmmaker’s work: a family of fishes raised by the same person that might resemble each other somehow.

- There is style of film: the particularities of the film/fish.

- And there is a stylistic history of cinema: the development of particular traits: eyes, fins, the swim pattern, etc.

- There are other things, such as the institutions that produce, distribute, and exhibit films: marines.

We can study how an individual fish looks like and its physiology or biology. This is called Textual Analysis.

We can study how a particular trait evolves in the species, eyes, fins, scales, particular body shapes; how do certain kinds of fish learn to emit light, electricity, poison, or ink. This is called Stylistic History.

We can study how a film is produced, promoted and circulated: this is called production/distribution/exhibition studies.

We can study how a film is received by its audience: Reception studies; how do the circumstances of moviegoing change and what does it mean: Spectatorship Studies.

How does a film make sense to its observer (how do we cook and eat the fish): Cognitive film theory.

What does one group of films have in common: Study of auteur, national cinema, cinema of a specific period, and so on.

How are gender, race, class and other cultural values represented in films: gender studies, cultural studies.

How does the species evolve over time: Historiography

How does fish compare to other sea animals? Comparative media studies (literature, theater, video game)

How does film relate to anything in the world such as staircase, mobile phone, snack, Greek history: I don’t have a name for this yet!

As you might have noticed—though I admit it can sound a bit dry—there’s so much more to film than just watching and forming a simple opinion about it. Film studies, much like film itself, is a wonderfully hybrid and open discipline. It invites us to explore a myriad of perspectives and, in doing so, often raises more questions than it answers. Each set of questions represents a unique approach to understanding this art form. However, I believe there are some fundamental questions that everyone should consider when engaging with films. These are the very questions we’ll dive into throughout this course!

What is the Nature of Our Experience in Cinema?

Roland Barthes, in an essay called “Leaving the Movie Theater,” writes the following:

There is something to confess: your speaker likes to leave a movie theater. Back out on the more or less empty, more or less brightly lit sidewalk (it is invariably at night, and during the week, that he goes), and heading uncertainly for some cafe or other, he walks in silence (he doesn’t like discussing the film he’s just seen), a little dazed, wrapped up in himself, feeling the cold-he’s sleepy, that’s what he’s thinking, his body has become something sopitive, soft, limp, and he feels a little disjointed, even (for a moral organization, relief comes only from this quarter) irresponsible. In other words, obviously, he’s coming out of hypnosis.

Later in the same essay, he writes (bold is mine),

This is often how he leaves a movie theater. How does he go in? Except for the-increasingly frequent-case of a specific cultural quest (a selected, sought-for, desired film, object of a veritable preliminary alert), he goes to movies as a response to idleness, leisure, free time. It’s as if, even before he went into the theater, the classic conditions of hypnosis were in force: vacancy, want of occupation, lethargy; it’s not in front of the film and because of the film that he dreams off-it’s without knowing it, even before he becomes a spectator. There is a “cinema situation,” and this situation is pre-hypnotic.

When it comes to watching films, we can think of two distinct modes of perception that shape our experience:

Hypnotic Mode

- This mode invites a passive, flow-based engagement with the film.

- It draws us into the narrative and character psychology, allowing us to become immersed in the story.

- Our evaluations here are subjective—it’s all about whether we like or dislike what we see.

- It feels akin to dreaming or being in a hypnotic state, offering a delightful, quasi-scopophilic pleasure—the joy of looking.

Analytical Mode

- In contrast, this mode encourages active, critical engagement.

- It demands our rigorous attention to the details that make up the film.

- We put in the voluntary effort to construct visual and auditory patterns, piecing together the film’s elements.

- Here, we delve into arguments, interpretations, and stylistic anomalies that beckon for explanation.

Think of it this way: if we were trained as doctors, our gaze upon a beautiful patient wouldn’t just stop at surface beauty. We’d appreciate how everything works harmoniously beneath the skin, recognizing beauty as a result of perfect functioning. We’d also notice subtle internal issues—those little cosmetic anomalies that only a skilled plastic surgeon might detect.

However, it’s important to note that there’s no strict boundary between these two modes; they simply represent different orientations. I wouldn’t say one is superior to the other. In fact, once you’ve honed both modes, you’ll find it easy to switch between them, enriching your film-watching experience!

What is a Film?

We often dive into discussions about film studies or our personal experiences with film, but have you ever paused to ponder: what exactly is a film? Is there something out there that exists independently of our unique perspectives that we can truly call a film? Is it the classic celluloid strip that flickers to life on the screen? Or perhaps it’s the digital file nestled on your hard drive, the one you snagged from the Pirate Bay? Let’s explore this intriguing question together!

Hollis Frampton, one of the most well-known avant-garde filmmakers, defines film as this:

…a film is anything that may be put into a projector that will modulate the emerging beam of light.

Imagine this: when you place your hand in front of a projector, it transforms into the film itself, blocking the light and creating a captivating experience. This idea is quite profound, isn’t it? It reminds me of certain film screenings—though they might not be as straightforward as Frampton’s own “lecture”—that evoke a similar sense of wonder.

A few years back, I had the pleasure of attending a mesmerizing 3D film screening by Ken Jacobs titled The Nervous Magic Lantern. Throughout the film, images danced before my eyes, pulsating gently and revealing stalagmite-like textures that shifted in and out of focus. The effect was nothing short of enchanting, creating a hallucinatory experience that felt intriguingly three-dimensional.

As I sat there, the soundtrack enveloped me with the familiar sounds of NYC subway platforms and the hustle and bustle of traffic. The film concluded with a charming scene of Jacobs himself walking upstairs, engaging in a lighthearted conversation with his wife about some mail. It was a delightful blend of visuals and sounds that lingered in my mind long after the screening ended.

At the end of the screening, Ken Jacobs reveals his trick.

He held up a curious piece of translucent plastic, an almost otherworldly object that contained small dark shapes nestled within, reminiscent of insects encased in amber.

Throughout the screening, he had been gently rotating and shifting this intriguing artifact in front of the projector, creating a mesmerizing spectacle that stirred both excitement and a touch of anxiety among the captivated audience!

But what about films that don’t rely on projectors? What do we call a film when there’s no projector in sight? If we follow the Frampton-Jacobs definition, it seems like most of what we watch on our laptops or TVs wouldn’t qualify as films at all!

So, let’s consider a broader definition that doesn’t hinge on the use of a projector:

A film is an audiovisual stream that engages its audience for a specific length of time.

However, this might be a bit too expansive. After all, it could imply that any AVI file is a film, and we know that’s not quite right!

So, how about we refine it just a bit? Here’s a more specific yet approachable definition:

A film is a concatenation of images, accompanied by sound, from which we recognize the objects in our world and the emotions within ourselves.

…

It’s interesting to note that I haven’t mentioned storytelling, photography, or even the human experience in my definition of film. By including these elements, we risk overlooking a treasure trove of remarkable films, like experimental works that don’t follow traditional narratives—take Frampton’s Zorns Lemma, for instance—or delightful animations (can we really say Mickey Mouse isn’t part of the film world?).

I must admit, I’m still not entirely satisfied with this definition. But that’s perfectly okay! As I mentioned earlier, our goal here is to spark curiosity about cinema, and I hope you’ll find your own unique definition of what a film truly is. The key takeaway is that by asking these questions, you’ll delve deeper into the essence of film, exploring its unique characteristics and the creative, expressive qualities it embodies.

For the sake of this course, let’s embrace the following formula:

image + motion + [sound] = sequence

sequence + [narrative] = narrative film

sequence + [arguments or ideas] = non-narrative film

What Truly Defines a Film…

If I had to choose one essential element for truly grasping the nature of film, it would undoubtedly be motion. No motion, no film — what you have is a picture.; add motion to that picture, and voilà—you have a motion picture, also known as moving images or movies!

There are countless ways to infuse motion into a picture, but I like to break it down into four main categories:

- Nature Motion: Think of the mesmerizing effects of sunlight, the gentle flow of water, the wispy dance of smoke, the ethereal quality of fog, the flicker of fire, the patter of rain, and the playful sway of the wind.

- Organic Motion: This encompasses the movements of plants, animals, and, of course, human beings—each with their own unique rhythm and grace.

- Medium Motion: Here, we consider the intrinsic qualities of the film medium itself, like the grain structure of celluloid, the flicker of a projector, and other fascinating artifacts that come into play.

- Cinematic Motion: This category includes the art of staging, the dynamic movements of the camera, editing techniques, and other innovative methods that bring a film to life.

Of course, this framework doesn’t quite capture the vital role of sound, which I like to refer to as “audiovisual motion.” But we can dive into the world of sound a little later!

Nature Motion

Motion from Nature is truly the most accessible concept to grasp. But how can you weave this natural motion into your photographic images? The renowned American filmmaker Maya Deren offers some insightful thoughts on this topic:

The invented event which is then introduced, though itself an artifice, borrows reality from the reality of the scene-from the natural blowing of the hair, the irregularity of the waves, the very texture of the stones and sand-in short, from all the uncontrolled, spontaneous elements which are the property of actuality itself. Only in photography-by the delicate manipulation which I call controlled accident-can natural phenomena be incorporated into our own creativity, to yield an image where the reality of a tree confers its truth upon the events we cause to transpire beneath it.

Some of the earliest films created by the Lumière brothers are remarkable for their ability to capture the dynamic movements found in nature, showcasing the world in a way that had never been seen before. These films, often just a few minutes long, present everyday scenes that highlight the beauty and spontaneity of life.

What is marvelous in the above footage is not only its intended protagonist, a baby laughing and playing, something universally evoking warmth and joy. It is equally important to take a moment to appreciate the surrounding elements, such as the rustling leaves swaying gently in the breeze.

Perhaps you recall the poignant scene from the film American Beauty, where one character (an aspiring teenager filmmaker) remarks, “You wanna see the most beautiful thing I ever filmed?” We are then presented with footages of a plastic bag flowing in the air, lifted up by the wind sometimes as if suddenly finding hope in life, only dropping to the ground again in the most helpless manner.

Organic Motion

Organic Motion, together with motion from Nature, are two kinds of motion can conquer the first movie audiences. At the turn of century one dancer named Loie Fuller became a superstar in the nascnent filmmaking business. Can you guess why? because she wears fancy dress that creates mesmerizing patterns of motion that occupies the entirety of early cinema’s vision.

Another example of the pleasure involved in experiencing motion, Norman McLaren’s Pas de deux:

Medium Motion

What I like to call medium motion refers to the unique movement introduced by the medium itself. Naturally, there are as many types of medium motions as there are mediums! We’re all familiar with that charming “vintage” film aesthetic, and many people find themselves drawn to a particular look that evokes nostalgia.

In our digital age, it’s true that kids born recently may never have the chance to experience the magic of real film, shot and projected using traditional film techniques. To them, celluloid film might seem like a relic from the 20th century, something best left in the past. However, the digital medium has its own distinct characteristics worth exploring. To honor the rich century-long history of film, let’s start with the film itself.

So, what kind of special motion does celluloid projection bring to the table?

The first is known as “grain structure.” Photographic film features a layer of randomly distributed tiny particles, created from silver halide that reacts to light. In each frame, this distribution pattern varies, resulting in an effect reminiscent of a swarm of tiny insects dancing around. Isn’t that fascinating?

Ernie Gehr created a fascinating film titled History in 1970, which is quite unique in its approach. He simply held a piece of black fabric in front of a movie camera, sans lens—what he referred to as “its image-forming device”—and illuminated the cloth with light. As Jonas Mekas beautifully put it, “History comes closest to being nothing but the reality of the film materials and tools themselves.” It’s a remarkable exploration of the essence of filmmaking!

Here’s how Ernie Gehr beautifully articulated his perspective on film: he views it as a “real thing” rather than merely an imitation.

In representational films sometimes the image affirms its own presence as image, graphic entity, but most often it serves as vehicle to a photo-recorded event. Traditional and established avant garde film teaches film to be an image, a representing. But film is a real thing and as a real thing it is not imitation. It does not reflect on life, it embodies the life of the mind. It is not a vehicle for ideas or portrayals of emotion outside of its own existence as emoted idea. Film is a variable intensity of light, an internal balance of time, a movement within a given space. -Ernie Gehr, January 1971

Another fascinating aspect of medium-specific motion is a phenomenon known as flicker. To put it simply, flicker is the strobing effect that occurs when the light gate of a projector is blocked. But why do we need to block it? Well, it’s essential for pulling the film strip to display a new image. If we don’t block the light during this transition, the image can become a blurry mess. Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope was marred by this very issue.

However, just blocking the light while the film advances isn’t quite enough. Through a bit of trial and error, it has been discovered that to perceive still images as flicker-free during projection, the frame rate needs to be around 50 frames per second (fps) in typical viewing situations. It’s important to note that 50 fps is considered the optimal rate for achieving the right amount of retinal illumination in a standard theatrical setting. While film cameras capture images at 24 fps, projectors must display those images at a higher rate to eliminate the flicker effect. This is cleverly accomplished by showing each image or “frame” twice, using a double-blade shutter (or a triple blade for 16 fps images). So, while one blade keeps the image steady, the second blade blocks the light gate, much like inter-image blocking does.

Although the second blade can be placed anywhere, in order to better mechanically balance the shutter it is placed symmetrically to the first blade (this is also why one blade shutter is not a good idea).

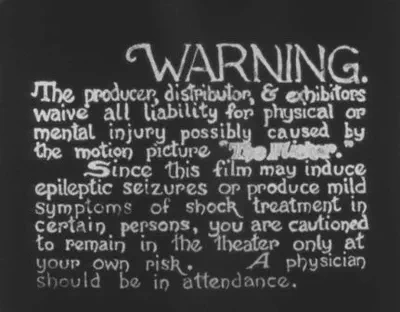

There is a film called The Flicker, made by Tony Conrad, that exploits this particular characteristics of film. The film has only 5 different frames, pure black, pure white, a warning frame, and two title frames. Throughout the film, it switches between black and white frames to produce stroboscopic effects.

The warning text read as follows:

WARNING. The producer, distributor, and exhibitors waive all liability for physical or mental injury possibly caused by the motion picture “The Flicker.”

Since this film may induce epileptic seizures or produce mild symptoms of shock treatment in certain persons, you are cautioned to remain in the theatre only at your own risk. A physician should be in attendance.

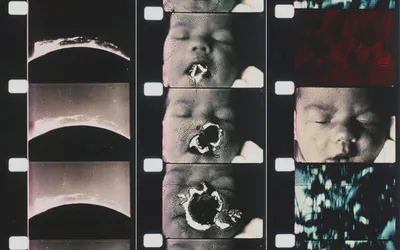

Medium artifact is a term I like to use when discussing the little imperfections that can pop up in a medium’s presentation. Each type of media has its own unique quirks, after all! For instance, with a celluloid strip, you might encounter dust, decay, scratches, and other charming flaws. On the other hand, digital files can present their own set of challenges, such as compression artifacts.

Take a look at the following MTV, which cleverly embraces compression defects as an intentional artistic effect:

Sometimes filmmakers draw on, or scratch the celluloid to create a bizarre effect. One who consistently practices this technique is Stan Brakhage.

One time, an optician, on looking into my eyes, said, “Well, by your eyes, physically, you shouldn’t even be able to see that chart on the wall, let alone read it. But, on the other hand, I have never seen a human eye with more rapid saccadic movements. What you must be doing is rapidly scanning and putting this picture together in your head.” … I wasn’t trying to invent new ways of being a filmmaker, that was just a byproduct of my struggle to come to a sense of sight. — Brakhage in an interview

Cinematic Motion

cinematic motion is what this course will focus on. Let’s start with some examples:

Mirror (1975)

Try describe what you see, the sensations brought to you by seeing motion.

Finally, a synthetic example of all kinds of motion mentioned above, an excerpt from Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep (1996)

Feature Film Presentation

It is customary for a film class to include a feature film screening every week. For this lecture, I recommend a film called Decasia, made by Bill Morison.

If you’re the kind of parent who enjoys intentionally introducing your kids to films which will cause loads of irreparable damage that years and years of costly analysis could never fix, I have just one word for you — Decasia

Bill Morrison’s production company is appropriately named Hypnotic Productions. When watching this film, think about the following questions:

- what kind of motions are involved here?

- how is the film made?

- who made this film?

- how are the sequences connected together?

- what is unique about this film?

Then try to describe your experience by answering these questions:

- Are you looking for a narrative? If yes is there? If yes what is it? Are there sections (acts)?

- How you engage with the film? Where do you spend your attention? Which part of the frame you look at? How do you assign meaning

- Why does it feel like intentional sometimes? That sometimes the decay induced visual patterns seem to work with the original images like a photo composite?

- What is the intention behind the sequence ordering? is there a visual theme? a narrative progression of sort?

- How does the sound work with the images?

- What is your emotional response (horror? sadness? liberating?)

More analytical questions:

- what exactly do you see?

- how do you make sense of the experience?

- what is neglected in your meaning-making process?

- what do you think the filmmaker’s intentions are?

- how does these intentions work with your expectations?

Finally, what is the purpose of the film (choose all that apply!)?

- induces psychedelic trance (or causes severe brain damage)

- proposes an alternative (and organic) definition of beauty

- reflects on the filmic medium, and film rhythm

- teaches film history (at least an intro to film history)

- urges us to support film preservation

- pays homage to the 60s avant-garde movement

- promotes an anarchist maxim “to destroy is to create”