Camera Movement in Max Ophuls

Max Ophuls as Conductor

Max Ophuls as ConductorBeing one of the most self-conscious stylists in the history of cinema, Max Ophuls’s films are known by their elegant and elaborated camera movements, which chime with decor and the acting performance to create repetition and rhythmic patterns both within and between films. Andrew Sarris is certainly not alone in praising Ophuls as “if all the dollies and cranes in the world snap to attention when his name is mentioned, it is because he gave camera movement its finest hours in the history of the cinema.”1 Camera movement, being an important aspect of Ophuls’s signature stylistics, seems to have attracted only too much attention, because again according to Sarris, the Ophulsian camera movement “is such a conspicuous element of film technique that Ophuls has never been sufficiently appreciated for his other merits.”2 The situation is somehow reversed now. Ophuls’s “other merits” have received detailed attention; his intricate social, gender and genre critique, his elaborate narrative as well as visual-aural style have been the subject of many fruitful scholarly works. Yet somehow his camera movement, the starting point, remains to be rigorously examined. This is not to say that scholars have been ignoring this aspect of Ophuls’s filmmaking. Quite the contrary; nearly all Ophuls scholars mention the camera movement at various points in their works. But the problem persists that these isolated and sometimes even casual observations do not amount to a proper methodology and are not informed by a theory for camera movement in general.

This paper is prepared with a larger project in mind, that is, a series of theoretical observations that have the moving camera as its sole object of examination. Therefore it is best to be read as a case study of the claims I will be making in this broader context. Nevertheless it is not a mere application of any theoretical framework, mine or the others, in that it seeks foremost to account for Max Ophuls’s individual artistic sensibility. To achieve this purpose I have discussed several examples of camera movement in Ophuls’s films, and how previously scholarships have treated them. The examples given are all fairly well-known so that they do not require a re-viewing. For the only example that is not so I have provided frame captures. The organization of this paper is as follows: first I discuss two modes of understanding camera movement and their respective relevancies to Ophuls’s works; then I present an alternative mode that tries to understand camera movement in terms of artistic sensibility; I also isolate a particular pattern of camera movement that is rather characteristic in Ophuls; finally I describe the directions in which I will expand this study.

Diegeticity and perception

Camera movement is by definition a diegetic event; although that is so, its mode of representation is different from other diegetic events in that the movement itself is never visible on the screen. In other words, when we say we see a movement of the camera, we never actually see a moving camera. What we see is movement in a broader category and we recognize a part of it as belonging to that of the camera. The invisibility of the camera is a kind of its own—it certainly is off screen; but, unlike other objects that are off screen, whose invisibility is temporary when the camera comes to their rescue, the camera’s invisibility is permanent. It would be wrong to attribute this invisibility to a mere inconvenience, for, when the chance comes where the camera can be seeing and seen at the same time (e.g., in front of a mirror), the camera invariably hides itself3. This ontological invisibility poses a risk for us, for whenever we talk about how the camera moves, we talk about something that is beyond our direct sight, something we can only infer, with variable degree of certainty. At any moment, the camera movement is viewed only in the sense that it is recognized through its point of view.

Historically, however, scholars have treated this invisibility as practically nonexistent. By relying exclusively on tracing back an observed movement on screen to a diegetic event, these scholars seem to suggest their meanings lie therein and a categorization as such would suffice to reveal these meanings. Barry Salt, for instance, insists on identifying and dividing camera movements by their diegetic nomination: pan, tilt, pan & tilt, track, track & pan, track & pan & tilt, and so forth.4 The following table is extracted from his “stylistic analysis” of Max Ophuls’s films:

| Year | Title | Pan | Tilt | PT | Track | Track&P | Track&PT | Crane | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | lachenden Erben, die | 17 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 43 |

| 1932 | Liebelei | 100 | 0 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 152 |

| 1936 | Komedie om Geld | 17 | 1 | 10 | 25 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 85 |

| 1939 | Sans lendemain | 39 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 30 | 5 | 1 | 92 |

| 1940 | De Mayerling | 48 | 4 | 4 | 18 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 95 |

| 1948 | Letter from an Unknown Woman | 67 | 2 | 14 | 22 | 59 | 10 | 10 | 184 |

| 1948 | Exile, The | 29 | 1 | 17 | 19 | 37 | 22 | 17 | 142 |

| 1949 | Caught | 23 | 2 | 12 | 30 | 65 | 25 | 0 | 157 |

| 1949 | Reckless Moment, The | 92 | 2 | 21 | 24 | 62 | 11 | 3 | 215 |

| 1950 | Ronde, la | 49 | 5 | 9 | 26 | 39 | 24 | 5 | 157 |

| 1952 | Plaisir, le | 87 | 4 | 28 | 17 | 72 | 42 | 31 | 281 |

| 1953 | Madame de … | 64 | 4 | 18 | 13 | 77 | 39 | 3 | 218 |

| 1955 | Lola Montes | 52 | 8 | 19 | 19 | 62 | 54 | 9 | 223 |

Despite Salt’s admirable confidence, I doubt if the accuracy of these data can be independently verified. I also doubt if anyone, including Salt himself, can use this data to account for our experience viewing the moving images, not to mention that the categories Salt needs to work with will become unbearably long if he wants (as I image he would) it to be exhaustive. Ultimately, what enables us to make sense of the movement is more important than the movement itself. For an obvious example that cannot be amply explained by resorting solely to the profilmic, what is the difference between a Steadicam shot and a crane shot, both have three dimensional mobility and both can be executed in fluidity? This said, I do not call for a total rejection to the set of terminology that labels such events. Nor do I suggest that film exists more in the spectator’s experience than in the form of an industrial product. But the fact remains that the two have their respective idiosyncrasies that deserve separate treatments. Like the notion of shot, the notion of pan, tilt, crane and others refer to communicative conventions vaguely defined, but nevertheless widely accepted. Furthermore, they can be traced back to some concrete details in the stage of production. What remains problematic is that a shot shot is not always a shot seen. All the profilmic events (acting, mise-en-scène , camera movement) converges at the point where locates the apparatus. All the postfilmic events (the construction of soundtrack, montage) converges at the point where locates the spectator, or his/her perception. These two stages have different ontological status and consequently follow different logic. In this essay, I am more interested in the significance of camera movement, that is, how we experience it.

What is this experience? Undoubtedly, in the lowest level, the experience consists of a visual perception of self-movement. David Bordwell, therefore, contends that “we need another model for describing camera movement, one that does not rely on a conception of some profilmic event through which, around which, toward which the camera is moved.”5 Bordwell in his article argues that we perceive camera movements through visual cues6, which enable us to distinguish in the images two kinds of movements: one that belongs to objects and one that belongs to the apparatus, the apparatus being either the optical camera in the profilmic scenario or its virtual counterpart in cases of animation films. To effectively explain visual perception, Bordwell suggests, various strands of cognitive studies might be good candidates. To examine camera movement from the perspective of visual perception brings up an important distinction that is partially masked if we regard camera movement solely as a diegetic event. A camera on the set moves in the absolute sense, but a camera movement perceived is always relative. A camera moving from point A in space to point B is pointless unless the two points have a different relation to other objects in this space. In other words, in physics movement alone creates space; but in cinema the movement is defined as perspective changes, and only becomes meaningful as such. As Bordwell points out, in animation films the camera, if they still use one, always stays there; in other occasions when the camera indeed moves, we do not necessarily perceive it. In a strictly perceptual basis, the task of perceiving apparatus movement is vulnerable to various potential disturbances. We do not always perceive it “right”, yet the result, that is, the “illusion”, is sometimes exactly what we need to perceive. Maya Deren’s Meshes of Afternoon, for instance, contains a shot of Deren ascending staircase where the rotation of camera choreographed with her movement creates a powerful illusion. Likewise, a cut that matches the action often escapes our attention since the illusion of the continuity masks the actual displacement. Clearly, Barry Salt’s taxonomy of Pans, Tilts or Pan-and-Tilts is not sufficient not only because it cannot be exhaustive (what about helicopter, Steadicam and all other future inventions), but that it cannot account for movement perceived as illusion.

While Bordwell’s essay points at certain directions where cognitive studies can bring light to our perceptual and emotional engagement with camera movement, he seems to imply that our understandings of camera movement as a stylistic element depend entirely on such studies. In various occasions, he denies that the camera movement can be “a trace of mental or emotional processes” or “a bearer of decisions or traits”7. This radical gesture seems strange given that Bordwell fully appreciates the link between a stylistic device and its conceiver8. Branigan critiques this position mildly as,

I will argue that our perception of, for example, the photographicity of an image, the motion of objects on the screen, and the motion of a moving camera onscreen cannot alone define what we mean by the concept of a ‘camera’ or how we use the concept of a ‘camera’ to explain our reactions to a motion picture. “Sense perception” is not enough. Indeed, our talk about a camera is firmly linked with our implicit knowledge of everyday practices, aesthetic discourses, film theories, and narrative theories. Our talk about film and the work of the ‘camera’ is not simply a rephrasing of “sense perception” (e.g., the camera pans left) but is already a modeling and projection of how a film and its ‘camera’ fit into our lives and system of values.9

If fruitful results have to wait until cognitive scientists have reached a consensus, it might not be an option for us in film studies. It is my opinion that meaningful investigations could be informed by but do not necessarily depend on cognitive terms. Moreover, even if cognitive studies have provided facts that relate to our experience of self-movement, the level of understanding might be far from immediately applicable to our cinematic experience, just like physics is uninformative to biology.

Sensibility, or the Ophuls touch

An alternative model of understanding camera movement will need to fuse its perceptual traits with the filmmaker’s intention to make them visible in the first place. In opting camera movement for editing, I believe the filmmaker often has a specific purpose, an expressive quality that he/she wants to bring out of the scene. The consistency of certain directors to use camera movement seems to suggest that these directors conceive the scene in a particular mode. It is therefore fit to suggest that this very mode is an important message that the filmmaker wants to deliver/express.

Max Ophuls is such a case in point. If theoretically the camera is capable of three functions: mobile framing, independent will of the camera as an embodiment of consciousness, expressive quality of the movement itself, in Ophuls’s films the last two categories are considerably more manifest. Mobile framing refers to camera movement’s basic function of rendering a change of framing in the diegetic space, often in order to maintain the immediate visibility of the action. But when the camera diverts from the purported main action and focuses its attention on seemingly minor or peripheral details, it ceases to grants our wishes to follow; by denying our will, it makes its own will known. In the “maison Tellier” episode of Le Plasir, for instance, when the camera refuses to enter the brothel, it not only marks a space whose boundary it can only hover above, but also makes it known that the camera does not always grant the spectator’s will. Naturally, this denial has to be justified one way or another. For Ophuls, who is known to favor a visual-verbal pun whenever possible, Paul Willemen’s interpretation marks a point in what he calls “a structuring literalism”.

So, the camera is on the side of the law (and of the people who cannot afford or pretend not to visit such places), but what has been excluded and repressed—in this case we see the repression and transformation of a verbal phrase [i.e., maison close] combined with the inscription of socio-sexual repression—returns and energizes the camera, moving it along as it obsessively circles its object of fascination, tracing the outlines of the gaps in the social fabric, catching glimpses of the forbidden areas where desire reigns. The tracks, dolly shots and crane movements constantly hold out the promise that in passing, or in the shift from one look to another… the look may find its object of desire, But never shall it be offered too detailed and close-up a scrutiny by a fixed gaze.10

What Willemen’s apathetic abstraction and blunt generalization fails to account for is the subtlety of the movement itself, which unfolds a multitude of emotional responses. Raymond Durgnat’s comment on a similar sequence in Rene Clair’s Le Quatorze Juillet (1933) is a healthy corrective.

When […] the camera moves along the outside of a house from window to window, one has a mixture of feelings—of cheeky wit (we are Peeping Toming in this Godlike way); of melancholy (we are outside the house); of intimacy (our partial exclusion emphasizes the privilege of catching them in secrecy); there is the absurdity of all these character so near to each other, and so self-engrossed; and the curious feeling of superiority in our magic gliding through mid-air.11

In Ophuls things get complicated since the mode of observation and the mode of identification often blend into a single camera movement, to the extent that these very notions become fallible. The opening sequence in Madame de… already shows what could perhaps be called a “distantiated identification”. A more radical example comes in Le Plaisir. In the third episode “the model” there is strikingly beautiful camera movement that visualizes the heroine’s suicide. The shot starts as static for 53 seconds when Jean (Daniel Gélin) taunts Josephine (Simone Simon)’s desperate threat. As Josephine starts to move, the camera first briefly pans left and then vehemently tilts down to the staircase; as the camera climbs the stairs, we see Josephine’s shadow projected on the wall in front of us, twice; finally we come to a locked window and Josephine’s right hand enters the frame from right to open it; the camera then approaches the window until its frames are out of frame; here we have an invisible cut; the next shot tilts down; another cut; tilts down from the same position, only faster; yet another cut, this time from a lower position and the camera descends onto the roof below. The whole segment of camera movement takes 20s. In regard to this sequence, Douglas Pye writes,

Up to the moment of her decision, Ophuls has framed the action in a static, observational take. In moving with her, the camera in a sense embraces her act, abandoning its observational mode. To this extent, at least, it 'identifies' with Josephine's action. But in doing so it also allows Josephine to leave the frame. Her movement motivates the camera’s but the camera can no longer see her.12

It is certainly true that before the suicidal volition emerges Josephine remains the object of the spectator’s observation. This movement abandons this mode of observation to “embrace her act”. But as my necessarily verbose description shows this is rather a coarse notion of what actually happens. Far from being invisible to the camera, she constantly enters the frame, by her shadow, by her hand that clear the passage for further movement of the camera. As what we have in Lady in the Lake (1946), the sequence displays a “virtual catalogue of contextual cues”13. But here exactly is the problem. If in reading a novel I encounter a passage saying “I climb the stairs, I jump out of the window”, I experience the movement in terms of ideas suggested to me by the words, in an imaginary world created in my mind. In cinema, however, if a camera movement enacts “I climb the stairs, I jump out of the window”, it presents a perspective in a concrete world that is not my mental construction. On the one hand, since the perception of this camera movement involves a perception of self-movement, it initiates a motor response in our body. This bodily response, along with other sorts of affective mimicry such as the perception of facial expression, gesture, posture and subtleties of voice, constitutes an active but virtual (suppressed, remain to be fully actualized) aspect of the cinematic experience. On the other hand, this cinematic bodily experience is never completely assimilable as in a literary experience (complete imaginary) or a real world experience (complete coalescence). Jean Mitry writes,

In the cinema, on the other hand, the so-called subjective impressions are presented to me—as is everything else: the camera moves down the street, I move with it; it climbs the stairs, I climb with it. I thereby directly experience the sensations of walking and climbing (at least this is my impression). Yet the camera is leading me, guiding me; it conveys impressions not generated by me. Moreover, the feet climbing the stairs I can see in the frame of the image are not mine; the hand holding onto the banister is not mine. At no point am I able to recognize the image of my own body. Thus it is obviously not me climbing the stairs and acting like this, even though I am feeling sensations similar to those if I were climbing the stairs. I am, therefore, walking with someone, sharing his impressions.14

What Mitry emphasizes is a sensation of co-movement accompanied by a conscious recognition of its alienating dimension. Instead of alluding to complete identification, Mitry writes, “these subjective images alienate me still further because they end up making me more aware than ever that the impressions I experience as mine have not actually been experienced by me.”15 In fact, this alienating effect is already registered in the speed and particular maneuver of the camera movement, which is far from identical to Josephine’s. The camera climbs the stairs with no jerky motion, as no human would have. Its turning (the pan), by contrast, is far too violent to be natural. The most conspicuous incongruence however, is the speed of the camera remains consistent while the shadow of Josephine shows that she moves noticeably faster and faster. Finally, the left pane of the window seems to open by itself; here the spectator’s suspicion amounts to a climatic confirmation: she cannot use her left hand because the camera is there. One might object that such nuances are insignificant. But insofar as our perception of movement is fully capable of distinguishing them, they are visible and do enter into our consciousness. Ultimately, I do not propose there is no identification involved in this camera movement, but rather, even in an apparently strong case of identification such as this, the camera still maintains a presence, a degree of independence, as we know in Ophuls the habitual mode of presentation is not identification but spectacle in distance.

Perhaps the independent will of the camera shows no better than in the famous staircase scene in Letter from an Unknown Woman. Instead of giving us a POV movement of Lisa (Joan Fontaine), Ophuls puts Lisa inside the frame, while “embracing her act” (Pye) and “sharing her impressions” (Mitry). If the convention of POV (Branigan believes this particular kind of setup is a variance of POV, and a less subjective but more stable one16) largely masks the difference for the first time, in the repetition the difference stands out all the more strikingly. It becomes, with the benefit of hindsight, a comment of the act that it purports to depict, as Andrew Sarris writes,

Ophuls’s camera slowly turns from its vantage point on a higher landing to record the definitive memory-image of love. For a moment we enter the privileged sanctuary of remembrance, and Letter from an Unknown woman reverberates forever after with this intimation of mortality. 17

Be it irony, sympathy, or otherwise, this kind of reading is possible only if the camera movement denies a conventional identification by calling considerable attention to itself. Being conspicuous it facilitates our registering the camera movement as a pattern that has its own right, so that it can be retained in the memory of the spectator and that he/she can recognize it upon repetition, a central theme for Ophuls. A readily assimilable movement, therefore, would be less effective to serve this purpose. Interestingly, Durgnat mentions another film of nearly the same year that features a similar usage of camera movement, Claude Autant-Lara’s Le Diable au Corps (1947).

Gerard Philippe’s first love-scene with Micheline Presle is climaxed by the camera tracking past a chequered bedhead to two hands clasping over the light-switch and each other. But later, as the heroine lies dying, in the same bed, giving birth to her lover’s son, the camera repeats the movement—this time, though, her hand closes over her husband’s, while she cries her lover’s name. And her husband takes it as the name she has chosen for their child…without the repetition of the camera position and movement, we would feel much less sharply the irony of deception and misunderstanding, the immortal moment denied and reasserted…18

There remains the third category, or properly speaking, the third aspect of camera movement that needs further elaboration. To understand this it is useful to bring up the analogy of calligraphy, in which the act of writing acquires a performative aspect. Calligraphy adds to the simple process of writing an expressiveness that is not contained in its final result, and cannot be explained by its practical meaning—the word as a linguistic signifier. I believe that this performative aspect is highly relevant in regards to camera movement. In fact, camera movement exists nowhere but in the performance per se. Like a dance, it is particularly elusive to verbal description. The end result of this movement—a composition, a shot of certain scale—does not disclose any information on its origin, or itinerary, since it can simply be inserted by montage. Also, it is almost inappropriate to regard a composition as the result of camera movement, or even its intermediary stage, because movement, as Bergson and Deleuze argues, does not exist there.

In calligraphy, one seldom finishes a word in one single stroke, not because it is technically impossible, but because the rhythm of writing is established rather by a smooth alternation of long and short strokes, of curves, straight lines and dots. This explains why Ophuls seldom uses sequence shot, which is not only far from technically impossible for him, but seems almost “natural” given his preference to mobility. Instead Ophuls often starts and ends a scene with long mobile shots and use rather fast paced editing in between. In general we observe that in Ophuls the mobility is either reserved for certain moments (emotional agitation, exertion of one’s will), reflexive on character relationships (who moves and who stays), and found in certain locations (dance hall, staircases). Otherwise, Ophuls is willing to let his camera stay put19.

The notion of camera movement as calligraphy also brings in further analogies such as writing, painting and music. Durgnat writes,

By his camera movements, Ophuls gives both visual life and emotional dynamism to the stuffy, hierachicalized, static décor—and society—of Vienna 1900. His camera moves past screens, flunkeys, fans, candles, whispered conversations, much as a Henry James sentence winds its way through innumerable reservations, concessions and hesitations to its final rather tentative assertion. 20

Bazin, in commenting on Henri-Georges Clouzot’s film, The Mystery of Picasso (1956), makes the following perceptive observation:

For during this work not a single stroke, not one patch of color appears-"appears" is the right word-in any way to be predictable. And conversely, this unpredictability implies the inexplicability of the compound-in this case the composition-by the simple isolation of its elements. This is so true that the whole idea of the film as a spectacle, and even more precisely as a kind of thriller, rests on our anticipation, on unceasing suspense. Each of Picasso's strokes is a creation that leads to further creation, not as a cause leads to an effect, but as one living thing engenders another.21

What Bazin notices as an unpredictability is in fact an essential quality of the spectacle as being an organically organized whole. This notion of organicity is I believe highly valuable in regards to Ophuls’s characteristic rendering of a cinematic spectacle as opposed to, say, the Hollywoodian mode of spectacle, whose logic is preconceived and totally predicable. Bertolucci, for example, articulates the following which may well be said by Ophuls:

For me the cinema is an art of gestures. When I find myself on a set, with actors and lights, the “solution” I find for a certain sequence, a certain situation, does not come from a pre-conceived idea, but from the musical rapport that exists between the actors, the lights, the camera, the space around them—and I move the camera as if I was gesturing with it.22

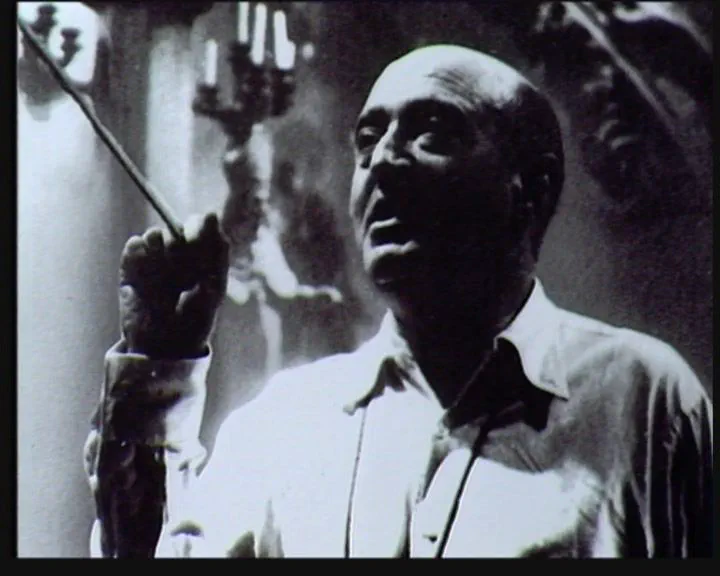

This leads to the idea that a director, much like an orchestra conductor, conceives the mise-en-scène as an organic rapport between different instruments and voices. It is certainly no accident that in Ophuls’s films the figure of conductor is not only seen, but often visually punctuated (Liebelei, Madame de.., Le Plaisir). The assistant director Tony Aboyantz to both Le Plaisir and Lola Montez told us that Ophuls used on set a stick much like a conductor’s baton, which he sometimes even carried to home23. Another anecdote comes from Eugene Lourié, art director for Ophuls’s Werther (1938). Lourié’s account unmistakably establishes that Ophuls directs a scene by its musicality.

When Ophuls broke down a script, he often annotated it by a series of musical symbols, marking the different modes and tempos of each scene. One scene might call for “allegro” or “allegro cantabile”, another “andante”, and so forth. And each change of mood would demand a different visual treatment of the given scene.24

Camera movement and editing

Camera movement is often perceived as, if not an opposite, an alternative to editing. When Max Ophuls was finally able to resume his career in Hollywood in 1941, his then rather highly developed insistence on the mobility of camera was in direct conflict with the so-called “classical” methods of analytical editing, which consists of a systematic alternation of establishing shots and close-ups. Although he enjoyed working with the skilled technicians and state-of-the-art dollies and cranes available at the studios, his wrangling with Columbia executives during the production of The Reckless Moment inspired the actor James Mason to rhyme:

I think I know the reason why / Producers tend to make him cry.

Inevitably they demand / Some stationary set-ups, and

A shot that does not call for tracks / Is agony for poor dear Max

Who, separated from his dolly, Is wrapped in deepest melancholy.

Once, when they took away his crane, I thought he'd never smile again.25

Elsewhere, the producer of Letter John Houseman recounts vividly how Ophuls is extremely reluctant (to say the least) to add two close-ups to the crane shot in the Vienna opera house. This shows that the matter is not altogether one of time and money spent (which Houseman tolerates out of their friendship), but rather, the potential editing threatens the aesthetics behind using a single crane movement to cover a complex scene. The threat is so real that once these close-ups are shot, they will inevitably turn up in the final assembly. Ophuls knows this, so he responds to Houseman’s request with “deadly hate”. On the other hand, for Houseman, although he acknowledges the “technical brilliance” of such a shot, he regards it “long, slow”, which “might prove tedious in what we all regarded as the weakest part of our film.”26

Nevertheless, Ophuls’s preference to camera movement has to be understood in a dialectic fashion. This is to say that he often combines other strategies, for instance editing and deep space staging, to bring out maximum expressive quality of the scene. In La Signora di tutti, when Gaby is expelled from the school and receives its full consequence (shame), the camera shows the father calling the sister into his study to announce Gaby’s imprisonment. When Gaby goes to the kitchen to clean up the dishes, the camera, instead of Ophuls’s signature style of floating through the walls, stays at the threshold of the corridor that leads to the kitchen. The result is a deep space staging where actions take place in the background, in the middle ground, instead of in the foreground. The added distance between the camera and the character and the fact that she is seen alone seeking the company of a dog conveys an overwhelming sense of helplessness, further strengthened by the father’s off screen diatribe, which dominates the space. It is as if the camera cannot bear to witness her emotional turmoil in a closer distance; it shows a “deep” sympathy, a strategy that is often seen in Mizoguchi.

Another example is the sequence of Donati and Louise meeting in the library in Madame de…, which uses almost exclusively continuity editing, all the more curious in a film where camera movements dominate. A close look at the sequence follows:

| No. | composition | dialogue | action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Figure 1 | How did you… | She runs into him and stops |

| 2 | Figure 2 | How did you know I was leaving? | She is visibly excited by his visit |

| 3 | Figure 3 | I didn’t know that…I came to assure you… | He turns to address her |

| 4 | Figure 4 | …and to thank you for your concern. | He moves to reveal the portrait on the left |

| 5 | Figure 5 | Do you like that picture? | She looks at the portrait of the husband, the Waterloo picture and him. |

| 6 | Figure 6 | She plays with her handkerchief | |

| 7 | Figure 7 | He looks at her without speaking | |

| 8 | As 6 | It’s the battle of Waterloo. | As 6 |

| 9 | As 5 | Waterloo, waterloo, bleak plain. | As 5 |

| 10 | As 6 | Over there is Blücher. | She gestures at the picture |

| 11 | As 7 | Yes. | He nods |

| 12 | As 6 | There on the right is Napoleon. | She gestures at the picture |

| 13 | As 7 | I would never have guessed. | He shakes his head |

| 14 | As 5 | Louise wipes her nose | |

| 15 | As 6 | If one has too much to say, words fail. | At the end of the shot she moves towards right out of the frame |

| 16 | As 5, with dolly in twice, arrives at Figure 8 | Why are you going away? Why not? Where will you go? The Italian lakes. Without me. Once there, I shall probably wonder at myself. Then, why? Yes, Why? | He moves toward her, dolly in; she sits down, dialogue; she then leans her head on his chest and he bows down to kiss her hair, dolly in again; lighting changes. They look up. The music stops here. |

| 17 | Figure 9 | The servant brings a lamp. | |

| 18 | My dear friend, I have been very reckless… | He explains the gift. Again she runs away towards right. |

From this visual decoupage it is fairly easy to see that Ophuls works to make shot #1 and # 3 a graphical match for #2 in order to suggest that Donati takes the place of the husband (even his posture, with left arm holding the coat and right arm straight, is identical to that of the husband). In the next shot, Donati literally comes in between Louise and the husband. Shot #5, however, reverts to emphasize the distance between the two, a distance that is virtually eliminated in the three previous shots by the use of long lenses. Their standing now reflects the notion of battle ground (the vast field between the two, the weaponry on the wall), where Blücher will flank Napoleon. Soon in shot #15 Louise raises the white flag and in shot #16 Donati marches toward her to the official surrender ceremony.

To have gone into considerable length about this scene I aim at three things: one, why it is impossible to use mobile camera in shot 1-15, all fairly short; and why shot 16 is relatively long and deploys mobile camera; third, what is the point of this alternation. First, if it is indeed possible to achieve the same graphic match through mobile framing (as Hitchcock did in Rope), the lengthy movement itself and the series of compositions that it generates will make the desired juxtaposition, especially their connotations, less instantaneous and conspicuous; what is more important, however, is that this scene needs to visualize a movement from conflict to reconciliation. The quick paced exchanges arouse so to speak a tension that is to be resolved in the final passionate reunion, although this reunion is soon to be broken again by the lamp of rationality or moral code. Dolly in, in this light, is appropriate because it conveys a smooth elimination of distance, a transition from two opposing sex to one creature with “with four arms and four legs and two faces” (Figure 8). Finally, camera movement and editing acquire saliency in their alternation. In this sense Ophuls’s sense of mise-en-scène can be described as contrapuntal.

This 2"08’ sequence is preceded by a mobile framing of Louise going down the stairs and running into the library; the final shot of this sequence sees the camera resumes mobile framing and uses a pan to the right to connect the next shot, which shows, in full motility, not only Louise going all the way the stairs to her room, but also the husband entering and walking into the library, closing the door behind him. I am tempted to call this bracketing camera movement, whose earliest usage can be attributed perhaps to Griffith’s Country Doctor (1909). In this film, Jon Gartenberg writes, “The panorama occurring at the beginning of that film and reversing itself at the conclusion creates a circular structure and infuses the film with an emotional power and an aesthetic unity.”27

Bracketing camera movement introduces to a sequence symmetrical motion, but the internal structure of this sequence remains to be defined by its own dramaturgical sense. As a consequence, it can feature typical continuity editing. The sequence in Caught (1949) where the two doctors exchange information on Leonora standing in their respective doorway is such an example. The shot starts with a rather high angle shot overlooking the desk (occupied by the heroine) from where the camera descends to the desk level and then pans left to frame Doctor Hoffman (Frank Ferguson), who is seen shaving with an electronic razor; the camera then quite conspicuously dollies in and pans right, turning around 120 degree to see Doctor Quinada (James Mason), who expresses his confusion by “she’s moved, gone.” Five shots of full shot scale follow; then ten shots of them in medium shot. The seventeenth shot gives us back Quinada in the full shot; the camera then reverses its trajectory: it dollies in and turns left to frame Hoffman, and then ascends to its starting position.

A similar rigorous pattern can be found in La Signora di tutti, where Anna comes to deliver the message for Gaby to come home. In this case between the two bracketing movements Ophuls uses a series of parallel tracking shots showing Leonardo in a car going to the left and Gaby in a boat going to the right. The point where they converge encompasses Anna, Alma, Gaby and Leonardo. In the opening shot Anna leaves; in the closing shot her position is taken by Leonardo. The symmetry of camera movement reinforces Leonardo’s role as a surrogate father to Gaby, since Anna is a messenger of the father.

As we can see, for Ophuls, a pair of bracketing movements can serve multiple purposes: it reestablishes a lost momentum that sometimes is necessary in a particular scene; it embodies what is physically absent in the scene; it accentuates what the mise-en-scène is already suggesting in terms of character relations.

In the above example from La Signora di tutti two camera movements are divided across shots in order to establish an alternation, or conversation. In other cases different camera movements are joined together to establish an illusionistic unity. In the waltzing scene of Madame de…, the camera follows the two lovers as they dance around over five nights, each night a new setting and costume, but always the same waltz. Here the continuousness of the movement is made possible, or rather the disruptiveness is masked by a constant “disturbance” in both the background and the foreground. Our involuntary attention on the couple—their facial expressions and their conversation—makes the dissolves almost imperceptible as if they were a part of the diegetic obstacles they constantly traverse. The music, especially the fact that the movement that we need to follow is executed in a continuous momentum helps to erase these perceptual gaps. Here is the sequence broke down in terms of camera movement.

| shot | Time marker | Location marker | Camera movement | transition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A hall with long tables arranged along the wall and food served | Slight dolly in with pan left | Cut to | |

| 2 | same | Pan right | Dissolve | |

| 3 | Four days | 2, with a military band (mainly brass) situated in the center, penned up by rectangular white balustrade; The conductor in the center always turns to face the couple. | The camera basically encircles the central rectangle, which is surrounded by four columns. The couple always moves between the white balustrade and the columns; therefore they are constantly blocked by these columns, as well as by dancers passing in the foreground. | Dissolve |

| 4 | Two days | 3, with statutes, paintings, “amusing” | This time the camera stays almost stationary, panning right | Cut to |

| 5 | same | same | A funny couple suddenly appears; the camera pans to the left to follow them; they disappear again behind a painting; the camera continues to pan left to pick up Donati and Louise. | Dissolve |

| 6 | 24 hours | 4, with plants, fountains and a glass cabinet in which woman musicians play violin, “sinister” | The camera retreats28, turns left, and then retreats again. | Dissolve |

| 7 | An empty hall with chandeliers and mirrors. In fact this is the same as the first location | The shot starts with an orchestra beneath a huge mirror, inside which we see the couple dancing; the camera pans around 180 degree left to follow the leaving violinist and to reveal the couple in long shot; it then dollies in to medium shot; the candle extinguisher appears in the background, the camera follows to the right all the way back to where the orchestra is located, until the harpist covers up the harp. | Fade |

What is interesting in this sequence is that, although the perceived intricacies of the overall motion on the screen make it difficult to identify the exact nature of the camera movements involved in these seven shots, these movements are not exactly complicated, technically speaking. They do create however an overwhelming sense of disorientation that is characteristic of waltz—which is a fascinating form of dance of endless possibilities based on a movement as simple as “turning around with the rhythm”. In waltzes what is vertiginous leads to what is immersive, that is, identifying with the movement itself. The reason why the camera has to keep them in the center of the frame, not too far, not too close, is to facilitate our identification with their movements; but this identification serves more to destruct a sense of orientation than to construct one. This double role of camera movement both as constructor the destructor of the space can be seen in a less radical form in The Reckless Moment, when Martin Donnelly (James Mason) first comes to visit Lucia Harper (Joan Benette) and reveals to her his possession of some letters that might implicate her daughter in a murder case. Robin Wood writes,

On the one hand we have been given, in unbroken moment, a tour of the entire open-plan layout of the downstairs of the house, the exact relation of kitchen to dining-room, dining-room to living-room, the various exits and possible entrances, all clear if we concentrate. At the same time, however, the continuous reframings, the camera's turns and returns, become so disorienting that all our confidence in knowing exactly where we are, in what direction we are facing, is undermined.29

Afterthoughts

Due to the scope of this paper many things have to be left out, which I intend to expand in the earliest occasion possible. In the place of afterthoughts I would like to describe what they are, at least those foreseeable to me already at the moment. First, the examples provided by this paper do not amount to, in my opinion, a satisfactory coverage, let alone be exhaustive. Ophuls’s oeuvre is substantial and the nature of my project determines that it cannot be restricted to a single film. A detailed verbal description of camera movement, however, is very “space-consuming”. In this paper I have tried to avoid verbosity, but not detailedness. In consequence I have not treated all instances that are significant. I feel this lack of evidence will probably impair the already meager arguments, which are doomed by the “case study” nature. Second, for a long time, for the relation between camera movement and narrative, the prevailing notion has been that camera movement needs to regard narrative as a point of reference to which it justifies itself, or otherwise it will be perceived as unmotivated. Jean Mitry is representative in this view,

The most important thing, in all cases, is that camera movement should be justified—physically, dramatically, or psychologically. Whether it is being used to track or is static, the camera must follow the action of a scene and not anticipate it. This law (to which we have already alluded) is basic in the sense that it is a function of the psychology of the spectacle and the expression. It does not legislate over any particular style or genre but over the whole area of expression: something cannot be described unless it already exists. To do so is to reveal the artificiality of the spectacle and thereby negate or destroy the fantasy it is trying to create.30

Obviously, something is wrong here. The Ophulsian spectacle does not shun from showing its artificiality and it prompts for a new conception of visual and narrative engagement in which the camera movement plays a vital part—it anticipates the action all the time. An expansion of this study therefore will include a section dealing with this issue. Finally, not much comparative analysis exists, which I deeply regret. I believe Ophuls’s sensibility is better explained when comparing his mise-en-scène of a particular situation to those of the others. This include, on the one hand, masters of mobile framing such as Mizoguchi, Welles, Jancso, Tarr, Angelopoulos; and on the other hand, filmmakers who rely on cutting, or filmmakers who avoid both cutting and moving. This may sounds too ambitious. My project makes no claim to answer all the questions. Yet its struggle to find answers would be worthwhile if only, by going through our options, the full value of the questions themselves can be better appreciated.

Works Cited

Bacher, Lutz. Max Ophuls in the Hollywood Studios. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

—. The Mobile Mise en scene: A Critical Analysis of the Theory of Long-take Camera Movement in the Narrative Film. New York: Arno Press, 1973.

Bazin, André. Bazin at Work: Major Essays & Reviews from the Forties & Fifties. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Bordwell, David. “Camera Movement and Cinematic Space.” In Explorations in Film Theory, edited by Ron Burnett, 229-236. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

—. Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Branigan, Edward. Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film. 66. Berlin: Mouton, 1984.

—. Projecting a Camera: Language-Games in Film Theory. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Durgnat, Raymond. Films and Feelings. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1967.

Gartenberg, Jon. “Camera Movement in Edison and Biograph Films, 1900-1906.” Cinema Journal 19, no. 2 (Spring 1980): 1-16.

Lourié, Eugene. My Work in Films. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985.

Mitry, Jean. The Aesthetics and Psychology of the Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Pye, Douglas. “Falling Woman and Fallible Narrators.” Cineaction, no. 59 (September 2002): 21-29.

Salt, Barry. Film Style and Technology. London: Starword, 1983.

Sarris, Andrew. The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Wexman, Virginia Wright, ed. Letter from an Unknown Woman. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Willemen, Paul. “The Ophuls Text: A Thesis.” In Letter from an Unknown Woman, edited by Virginia Wright Wexman and Karen Hollinger, 271. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Wood, Robin. “Plunging off The Deep End into The Reckless Moment.” Cineaction, no. 59 (September 2002): 14-19.

Sarris, The American Cinema. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

The movement known as direct cinema constitutes a challenge to this very notion. ↩︎

Salt, Film Style and Technology. ↩︎

Bordwell, “Camera Movement and Cinematic Space,” 229. ↩︎

The use of word “cue” here relates to Bordwell’s theory of cinematic narration and hence can be regarded as an effort to associate these two aspects of filmic experience. On the other hand, visual perception obviously operates on a different level than narrative comprehension. ↩︎

Bordwell, Making Meaning, 234. ↩︎

Otherwise his study of cinematic staging would not have been divided by authors but rather by, say, “perceptual types”. ↩︎

Branigan, Projecting a Camera, 33. ↩︎

Willemen, “The Ophuls Text,” 271. ↩︎

Durgnat, Films and Feelings, 75. ↩︎

Pye, “Falling Woman and Fallible Narrators,” 23. ↩︎

Branigan, Projecting a Camera, 66. ↩︎

Mitry, The Aesthetics and Psychology of the Cinema, 270. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Branigan, Point of View in the Cinema, 110. ↩︎

Sarris, The American Cinema. ↩︎

Durgnat, Films and Feelings, 119. ↩︎

See my measurement of camera movement in Ophuls’s two films using the cinemetric tool. http://www.cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3224. (Madame de…)

http://www.cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3222. (La Ronde)

You need to enable color code in order to see how mobile shots alternate with static shots. ↩︎

Durgnat, Films and Feelings, 76. ↩︎

Bazin, Bazin at Work, 167. ↩︎

Bacher, Max Ophuls in the Hollywood Studios, 79. ↩︎

In criterion’s DVD release of Le Plaisir, there is an interview of Tony Aboyantz where several pictures of Ophuls with his baton are shown. One of these pictures is used in Godard’s Histoires du cinéma, 1A. See cover image. ↩︎

Lourié, My Work in Films, 62. ↩︎

Bacher, Max Ophuls in the Hollywood Studios, 1. ↩︎

Wexman, Letter from an Unknown Woman, 20. ↩︎

Gartenberg, “Camera Movement in Edison and Biograph Films, 1900-1906,” 16. ↩︎

I suspect that this shot is done by an overhead track with suspended platform, like the swamp scene in Sunrise. ↩︎

Wood, “Plunging off The Deep End into The Reckless Moment,” 16. ↩︎

Mitry, The Aesthetics and Psychology of the Cinema, 259. ↩︎