The Work of Writing in the Age of AI

Three Stages of Writing Technology

Writing is an ancient craft that blossomed when humans first invented written language. Since that moment, the act of writing has always been intertwined with technology—the tools we use to bring our thoughts to life. From the ancient oracle bones and cuneiform tablets to papyrus and rice paper, this rich tradition continues to thrive today, as I’ve explored in another article.

What’s the most fascinating part of this story? The tools for writing are in a constant state of evolution! Broadly speaking, the technology behind writing has gone through three distinct stages.

The first stage is marked by the use of sharp objects that leave a trace on various surfaces. This innovation allowed writing to coexist alongside painting, as for a long time, these two forms of expression shared the same technological foundation.

The second stage of writing technology is ushered in by the invention of the typewriter, which has evolved into today’s computer keyboard. The typewriter made its debut in the 1870s, but it wasn’t until several decades later that it truly took off, as improvements were made to enhance its reliability and portability. Since then, it has firmly secured its place in the image of a writer’s workspace.

One of the most significant advantages of the typewriter, compared to earlier writing tools, is the dramatic reduction in the effort required for training. Gone are the days of spending years honing your calligraphic skills just to produce a presentable piece of writing.

If you do receive some training, typewriting offers an additional perk: speed! With practice, typing can become incredibly fast. A professional typist can achieve impressive speeds of 150 words per minute, a feat that handwriting simply can’t match.

I believe we are on the cusp of entering an exciting new era in the realm of writing, which I refer to as the third stage: AI-collaborated writing. This stage represents a significant evolution in the way we create written content, blending human ideation with the wordsmith power of language models. However, before we delve deeper into this transformative phase, let us take a step back and examine the fundamental processes involved in writing itself.

The Importance of Being Messy

In our quest to create digital tools that replicate tasks once done by hand, we often find ourselves chasing after perfection and speed. The metaphor of the machine age—where digital technology serves as a virtual counterpart—paints a picture of smooth, shiny, and stainless steel or glass. Almost instinctively, this becomes our ultimate goal.

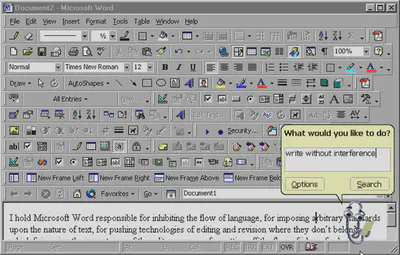

We’ve already touched on how the typewriter can produce flawless results with minimal training. But is that pristine presentation truly beneficial for writing, or can it sometimes become a source of frustration? There’s something almost mechanical about the typewriter’s relentless rhythm, churning out one word after another with unwavering precision.

The advent of computer initially only duplicated what the typewriter can do and just made it more flexible — you can easily maintain the immaculate look of your work no matter how many times you have gone back to change the words. We normally think of this as an advantage , but it also eliminates many important ways we can transfer our thinking into words.

Our thoughts are not cleanly delineated. They are a tangled, messy network of interconnected ideas. Writing is about shaping this tangled mess, or to put it in more accurate terms, about helping this mess to take shape by itself. The messy look of a manuscript therefore is a faithful picture of our mental work. It may be less presentable, but it shows the work, with its many traces; it is a living proof of the work, which is not the end result but the process. In addition, it does have this satisfying effect: the messiness serves as a reminder that I have done work.

Even a typed manuscript seems to convey more work than the printouts from a word processing software. A few years ago in my research I sometimes have to read PhD dissertations published in the 1970s. These are all typed manuscripts and looked very different from what came after: pages with varied fonts and elegant layout. But a typed manuscript seems to beg me to hear the relentless clicking sound, and to feel the excitement and frustration behind these monotonous looking pages.

Converting a sheet of paper to digital bits that can be manipulated by algorithms has many advantages. It is precise; and it is infinitely duplicable. This is why nobody is using a typewriter anymore. However, we seems to swallow all too easily the negative aspects of this progression — most of us are not even remotely aware of the loss, for the simple reason that this may be the only writing tool you’ve ever used.

Writers each have their own unique writing habits, shaped by various factors like the type of paper or pen they use, as well as the ambient noise and lighting around them. I remember watching a fascinating documentary about Marguerite Duras, and one scene stuck with me: it captured her workspace, a small room with a tiny desk at its center, surrounded by stacks of books scattered across the floor. I tried to find that exact image online but came up empty. However, I did stumble upon a similar one featuring Susan Sontag. This made me wonder if having books piled on the floor is a common quirk among certain writers. Could it be that they simply didn’t have room for a bookshelf?

There are of course those who prefer to write outside a cozy corner surround by books. Why did Hemingway chose to do his writing in a coffee shop? Because he couldn’t afford a writing desk at home?

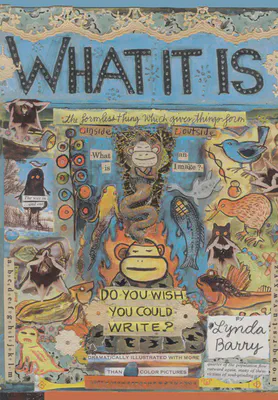

There are countless stories about writers and their unique preferences for stationery, and it doesn’t have to be Moleskine and Montblanc! I remember reading about a renowned Chinese writer, Yu Hua, who began his writing journey on discarded envelopes. The tactile sensation of those envelopes must have been a key component in his writing process, because as he started to write more and more, he eventually ran out of them! What is it about those humble, used envelopes that can ignite a writer’s imagination and get the words flowing?

Beneath this surface diversity there is common ground; the writing process is one filled with sensational inputs. To write is to be surrounded with tangible or intangible things, no matter these things are presented in the form of stack of books, scraps of papers, a folder of text files, lively voices, or something entirely invisible, such as ideas. If this is the essence of writing, then how can we possibly create in a sterile glass room, perched at a stainless steel desk?

In recent years, the concept of “minimalistic” writing tools has taken the world by storm. With a constantly evolving array of apps promising a “distraction-free” writing experience, I won’t dive into specifics here. But the basic idea is simple: display nothing but the text you are currently typing on, all with beautiful typography.

Is it an improvement from the cluttered tool that we have been using for writing? Yes it is!

The concept behind all these distraction-free writing tools is simple: why get caught up in formatting our words before we’ve even had a chance to write them down? Sure, formatting has its place, but it should come after we’ve poured our thoughts onto the page. In fact, it might be better suited for someone other than the writer to handle!

But let’s pause for a moment and ask ourselves: is this really the best we can do? Can digital ink offer anything more than a mere replica of a blank sheet of paper? Is that blank canvas truly the ultimate support for aspiring writers?

What Do We Really Need When We Write?

Like many people my age, I began my writing journey with good old pen and paper. However, it didn’t take long for me to embrace the digital age once computers became more affordable. I’ve had my fair share of experiences with word processors, and honestly, choosing a computer over a typewriter was a no-brainer—especially since typewriters were already fading into the background as I grew up.

During my graduate studies years, I discovered a fantastic tool called Scrivener, and it completely changed my writing process. It is primarily marketed in certain areas such as movie script or novel. But it has been used for many other long form writing. Scrivener offers something that’s both more and less than traditional word processing. While word processors, as one of the first wave of personal computer applications, are designed primarily for composing and presenting text, they often emphasize formatting and layout. This focus on presentation is largely driven by business needs; after all, just having text isn’t enough—it needs to be visually appealing to be deemed useful.

But what about writing novels or tackling lengthy non-fiction projects like dissertations? It was during my often frustrating search for a better tool for dissertation writing that I truly appreciated the utility of Scrivener.

For dissertation, or any kind of book-length argumentative writing, the main challenge is to shape your (hopefully) highly original idea (we like to call it argument, as it often is). This idea can be summarized in a few sentences (again, hopefully!) and then expanded, with substantial details and references, to the length of the entire book. Each chapter should contribute to the overall idea in a rigorous, logical and coherent way.

The above description says nothing about the subject matter, your writing style, or any word-level crafts you may or may not have. This is a good thing. Because a tool should be able to help everybody who wants to write a dissertation, regardless of the topic, style. So where is the challenge? The reality is that when you start, or when you are in the middle of research, all the topics and ideas that have come to occupy your mind can be best described as a shapeless mess: some are promising but not entirely convincing; some are vague; some are solid but do not seem to be highly relevant, etc. Writing a dissertation is not really about writing, but rather, about thinking through an issue with the help of writing things down.

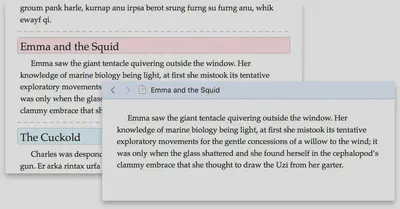

What Scrivener does is nothing super fancy. It simply gives you a folder like structure where you can organize these small chunks (rtf files). It makes it easy to split one chunk into two, or to merge two chunks into one. It also has the functionality of showing you all the separate chunks together in one continuous document, as if they are paragraphs in this one document — called scrivenings mode. Scrivener also has a lot of other features (such as setting target, tracking) that I find less useful to my case.

Can you start writing your dissertation with Microsoft Word? Yes you can, and I believe there are a lot of people who used nothing else. But the challenge is obvious. You need to carry a lot of intellectual processes in your mind, because as soon as your Word document goes beyond a certain length (20–30 pages) it becomes difficult to understand what is going on.

Not everyone needs to write a doctoral dissertation, but the process is similar. If you want to write any decent length essay, the challenge is never crafting individual phrases, but rather, organizing small chunks of writings into a flow of ideas. Scrivener does two key things to help:

It simplifies the writing process by stripping away non-essential elements during the often lengthy composing stage, focusing on the essentials of a straightforward rich text format.

Unlike the so-called minimalist trend, which assumes you have everything figured out and just need a distraction-free space to churn out your thoughts, this approach recognizes that you might need a little extra help to get those ideas flowing. It understands that you want to keep all your writings and research close at hand without having to leave your writing environment. That’s why it introduces features that traditional word processors often leave to the operating system, such as folders, tags, and the ability to view your work side by side.

Scrivener was an incredible ally during my journey of writing my dissertation, which was my very first book-length project. I ended up generating so much content that only about ten percent made it into the final published version. And that’s perfectly fine. I learned, years later, through the Zettelkasten method, that ideas embark on a long and winding journey. From that initial spark of inspiration to establishing connections, adding reflections, and ultimately shaping them into a cohesive argument, the process can take many unexpected turns.

It would be a bit naive to start writing as if you know exactly where everything will fit. If you feel that way, then I must say, you’re lucky! For me, though, it’s all about finding that fertile ground to plant the seeds of my ideas. Who knows what they might grow into? It could be something entirely unexpected, and that’s perfectly fine!

Fastforwarding to many years later, I started to use Notion and then lately changed to Obsidian. In essence, these tools are not much different from Scrivener, except that instead of using the RTF, they use the Markdown format. Both systems, of course, are built on this framework that allows extensions to enhance their own abilities. In the case of obsidian, these are called plugins. Plugins are a very powerful extension of the core functionality of the system. But most of are still geared toward organization and presentation.

This is why I in my view, Notion or Obsidian did not make a new generation of tools. They excel at organizing notes and customizing the way these notes look. However, we haven’t really made significant progress in helping writers to write better.

And this is I think how the rise of AI signifies a new stage in writing technology.

Writing as a Case of Augmenting Human Intellect

Thoughts often feel vague and fleeting—like wisps of smoke just out of reach. Sometimes they crystallize into clarity, demanding to be written down. Other times, they linger in the background, waiting for a spark of insight to bring them forward.

Writing, especially fiction (which I’m still new to), feels like an adventure. It’s both a way to create and to discover a home for my thoughts. It mirrors how our minds work: we forget, learn, make new connections, and rearrange what we know until the familiar looks new again.

For a writer in the digital age, the most important thing is not the tool that helps you to input the text, be it typewriter, keyboard, or a text editor. It is a rich but virtual context in which a writer can produce thoughts, connect thoughts. It is a mechanism to turn ideas into words. or to be precise, writing itself is this mechanism and technology is there to facilitate it.

What often happens is that what should be a starting point gets mistaken for the destination. While eliminating distractions is certainly a wise move, we should also consider what truly benefits the aspiring writer. Can technology actually enhance the writing process, or is it better to hand them a blank sheet of paper and simply hope for the best?

Several visionary thinkers have shaped my perspective on this topic. One of the most influential is Vannevar Bush, an engineer and scientist who penned the groundbreaking article “As We May Think” in 1945. In it, he envisioned an advanced technological system designed to assist researchers like himself. Following in his footsteps, Doug Engelbart, the brilliant mind behind the invention of the computer mouse, further explored these ideas in his 1962 treatise “Augmenting Human Intellect.” While Engelbart didn’t specifically address the writing process, he provided an in-depth look at a system that could empower architects in their work.

Let us consider an augmented architect at work. He sits at a working station that has a visual display screen some three feet on a side; this is his working surface, and is controlled by a computer (his “clerk”) with which he can communicate by means of a small keyboard and various other devices.

He is designing a building. He has already dreamed up several basic layouts and structural forms, and is trying them out on the screen. The surveying data for the layout he is working on now have already been entered, and he has just coaxed the clerk to show him a perspective view of the steep hillside building site with the roadway above, symbolic representations of the various trees that are to remain on the lot, and the service tie points for the different utilities. The view occupies the left two-thirds of the screen. With a “pointer,” he indicates two points of interest, moves his left hand rapidly over the keyboard, and the distance and elevation between the points indicated appear on the right-hand third of the screen.

Now he enters a reference line with his pointer, and the keyboard. Gradually the screen begins to show the work he is doing — a neat excavation appears in the hillside) revises itself slightly, and revises itself again. After a moment, the architect changes the scene on the screen to an overhead plan view of the site, still showing the excavation. A few minutes of study, and he enters on the keyboard a list of items, checking each one as it appears on the screen, to be studied later.

Ignoring the representation on the display, the architect next begins to enter a series of specifications and data — a six-inch slab floor, twelve-inch concrete walls eight feet high within the excavation, and so on. When he has finished, the revised scene appears on the screen. A structure is taking shape. He examines it, adjusts it, pauses long enough to ask for handbook or catalog information from the clerk at various points, and readjusts accordingly. He often recalls from the “clerk” his working lists of specifications and considerations to refer to them, modify them, or add to them. These lists grow into an evermore-detailed, interlinked structure, which represents the maturing thought behind the actual design.

Prescribing different planes here and there, curved surfaces occasionally, and moving the whole structure about five feet, he finally has the rough external form of the building balanced nicely with the setting and he is assured that this form is basically compatible with the materials to be used as well as with the function of the building.

Now he begins to enter detailed information about the interior. Here the capability of the clerk to show him any view he wants to examine (a slice of the interior, or how the structure would look from the roadway above) is important. He enters particular fixture designs, and examines them in a particular room. He checks to make sure that sun glare from the windows will not blind a driver on the roadway, and the “clerk” computes the information that one window will reflect strongly onto the roadway between 6 and 6:30 on midsummer mornings.

Next he begins a functional analysis. He has a list of the people who will occupy this building, and the daily sequences of their activities. The “clerk” allows him to follow each in turn, examining how doors swing, where special lighting might be needed. Finally he has the “clerk” combine all of these sequences of activity to indicate spots where traffic is heavy in the building, or where congestion might occur, and to determine what the severest drain on the utilities is likely to be.

Much of what Engelbart discussed is already a reality. Since the 1980s, we’ve witnessed a remarkable surge in computer tools designed for business applications—think document collaboration, seamless communication, and efficient project management. However, when it comes to other areas of work, particularly the more creative and solitary pursuits like writing, the progress hasn’t been quite as pronounced.

So, let’s take a moment to reimagine what the future could hold for writers. What exciting possibilities might unfold? (the following scenarios are generated by AI)

Scenario 1: Weaving Worlds in Kepler-186f

Kai leaned back, the glow of the holographic interface reflecting in his eyes. He was deep in the tangled nebula of his space opera’s third act, set on the ochre plains of Kepler-186f’s second moon. His protagonist, Captain Eva Rostova, was cornered, her motivations fraying under duress.

Accessing the Deep Lore: “Remind me,” Kai murmured, tapping a specific icon beside Eva’s character portrait hovering in a side panel, “what’s her core drive when facing betrayal?” Instantly, the system cross-referenced its vast internal knowledge base – the project’s living heart, meticulously cataloging every character quirk, planetary detail, and technological McGuffin Kai had ever conceived. It highlighted the entry: Eva Rostova: Primary Motivation (Extreme Stress) -> Protect Crew At All Costs (Overrides Personal Safety protocols, linked to Incident Gamma-7). The system knew this because Kai had painstakingly built out Eva’s profile weeks ago, linking events and traits within this integrated wiki. It even noted this trait was consistent across the planned trilogy, drawing from the shared series data.

Painting the Scene: Kai typed: Eva scanned the canyon ridge. Bland. He highlighted the sentence. A subtle prompt appeared: Enhance Description? Kai nodded. The system, understanding the arid, alien setting logged in the world-building section of its knowledge base, offered three alternatives. He selected one: Eva’s gaze swept the sun-baked ridge line, where shimmering heat-devils danced above jagged, rust-colored spurs of rock. That was better; the system understood the feel he was going for, drawing on the genre conventions and desired style he’d defined earlier.

Breaking the Impasse: Eva needed to escape, but how? Kai felt the familiar tendrils of writer’s block. He placed the cursor at the end of the last paragraph and activated the narrative continuation function. Drawing context from the preceding text, Eva’s established character traits (from the knowledge base), and the overarching plot points stored in the timeline view Kai had previously structured, the AI generated a plausible paragraph: Her hand instinctively went to the emergency transponder on her belt, its activation sequence a desperate gamble against the jamming field she suspected the bounty hunters had deployed… It wasn’t perfect, but it sparked an idea for Kai.

Refining the Moment: Kai wrote Eva activating the device, but the description felt weak. He highlighted his clunky sentence and triggered the rewrite function. Instantly, four variations appeared, each offering a different nuance – one more desperate, one more technical, one focusing on the sound, another on her physical action. He picked the most visceral option and tweaked it slightly.

Ensuring Consistency: Later, writing a flashback, Kai described a ‘Phase Cloak’ device used in Eva’s backstory. As he typed the term, the system subtly highlighted it. Clicking revealed a contextual note pulled directly from his internal wiki: “Phase Cloak (Mark II): Standard issue Star Command stealth tech pre-Incident Gamma-7. Known weakness: Vulnerable to gravimetric pulse detection." This seamless check ensured he didn’t contradict his own established lore, the AI acting as a vigilant guardian of his world’s intricate rules without him needing to manually search or remember every detail.

Throughout the session, Kai rarely had to copy-paste context or explain basics to the AI. Whether he was using the inline suggestions, consulting the dynamic timeline, or fleshing out details in the deep lore engine, the system seemed to breathe his story alongside him, understanding the characters, the world, and the narrative threads, allowing him to focus purely on the creative act of weaving his intricate universe.

Scenario 2: Charting the Frontiers of Gene Editing

Dr. Lena Hanson stared at the blank document, the task ahead daunting: synthesizing the last two years of rapid advancements in CRISPR gene editing into a coherent review article. She needed structure, comprehensive coverage, and alignment with the field’s current trajectory.

Mapping the Intellectual Landscape: Lena initiated a new project within her research assistant platform, defining her core topic: “CRISPR-Cas9 Therapeutic Applications & Challenges, 2023-2025.” The system went to work, not scraping websites, but analyzing the citation network and content of high-impact publications within that specific scholarly domain. Within minutes, it presented a detailed breakdown: dominant research themes (delivery systems, off-target mutation analysis, specific disease applications), frequently debated questions appearing in recent literature, crucial statistics cited across multiple key papers, and even the common structural patterns (section headings like ‘Mechanism Refinements,’ ‘Ethical Considerations’) used in top-tier journal reviews on similar topics.

A Data-Driven Blueprint: Based on this deep analysis, the system generated a comprehensive content outline. This wasn’t just a generic template; it was a dynamic roadmap suggesting specific sub-sections reflecting the identified themes, prioritizing areas receiving significant recent attention, and listing key questions her review should aim to address to be relevant. It even flagged several seminal papers from the analysis as ‘must-cite’ references for specific sections.

Accelerated Information Synthesis: Lena had a folder bursting with relevant research papers – dozens of PDFs representing months of reading. She imported the entire folder into the system. Instead of manually sifting through each one again, she used the platform’s integrated PDF analysis tool. “Summarize the key findings regarding lipid nanoparticle delivery in this paper,” she queried one PDF. Instantly, a concise summary appeared. For another, “Extract statistics on off-target mutation rates reported in the Results section.” The system pulled the relevant figures, saving her hours of painstaking re-reading and note-taking.

Guided Writing with Real-Time Insights: Lena began drafting the section on ‘Delivery Vector Innovations’ directly within the platform’s editor, which seamlessly synced with her preferred Overleaf environment via an integration. As she wrote, a real-time ‘Scholarly Relevance’ score updated dynamically in the sidebar. It compared her draft’s thematic coverage against the patterns identified in the initial literature analysis. The score dipped. The system highlighted a gap: “Consider expanding on recent developments in adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector engineering – prominent theme in 4 of the top 10 relevant papers.” It suggested specific concepts and even pointed to relevant paragraphs within the PDFs she had imported earlier.

Refining with Academic Precision: She drafted a sentence explaining a complex enzymatic interaction, but it felt convoluted. She highlighted it and used an AI rewrite function specifically tuned for academic language. It offered several alternatives, maintaining the scientific accuracy but improving clarity and conciseness, adhering to the formal tone expected in scholarly publishing. It effortlessly handled the specific jargon and sentence structures common in her field.

For Lena, the process felt like she was engaged in a structured dialogue with the current state of research. The system provided a data-informed framework, accelerated information retrieval, offered targeted suggestions based on established knowledge, and helped polish her prose to meet academic standards, all integrated directly into her existing writing workflow. The final manuscript wasn’t just her synthesis; it was demonstrably aligned with the core concerns and structure of the research frontier she aimed to document.

Scenario 3: Weaving the Story of Sustainable Travel

Maya faced the digital canvas, the cursor blinking like a patient collaborator. Her mission: craft a vibrant article on sustainable travel. The topic sprawled before her, a landscape needing paths.

Seeding the Structure: She began not with an outline, but with a feeling – typing a single paragraph capturing the quiet joy of connecting with a place responsibly. She offered this seed to her writing partner, the AI writing app. It seemed to grasp the essence immediately, branching out threads of thought – eco-lodges, mindful journeys, community connections. It didn’t just list them; it suggested a natural pathway through the topic, laying out distinct sections like stepping stones across a stream. Maya nudged the stones, rearranging the flow, tagging each with quick digital notes—reminders of specific anecdotes or data points she wanted to weave in later.

Adding Depth and Detail: Diving into the section on ‘Eco-accommodation,’ she described lodges powered by sun and wind. Feeling the description was still too thin, a bit skeletal, she prompted the app to expand on the idea. Like a skilled assistant anticipating her needs, it seamlessly wove in a new paragraph discussing water conservation and locally sourced building materials, perfectly echoing her voice and the narrative’s rhythm. Wanting a touch of external validation, she asked the app to consult her personal library – a digital scrapbook of clippings, quotes, and inspirations. Instantly, it surfaced a poignant quote from a renowned conservationist, fitting the context perfectly. She dropped it in with a tap.

Refining the Article’s Shape: Satisfied with that section for now, she zoomed out. The interface shifted, transforming from detailed text to a condensed map of her article, each section distilled to its core idea. Alongside this overview, a dynamic visual representation of the article’s shape pulsed gently. It was immediately obvious – one area, focusing on the downsides of mass tourism, cast a much larger shadow than the sections focused on hopeful solutions. The balance felt off. With a simple gesture on the screen, she divided the oversized section, calving off a new block dedicated entirely to proactive solutions for over-tourism.

Harmonizing the Voice: Reading through the condensed overview, she noticed one of her earlier sections sounded distinctly more formal, almost stiff, compared to the warmer tone emerging elsewhere. She highlighted the summarized thought and gave the app a simple instruction: “Make this flow more naturally, more invitingly.” The underlying text shimmered and reformed itself on the detailed view, adopting the warmer tone of the surrounding narrative while meticulously preserving her original meaning and insights.

Finally, she zoomed back into the immersive, sentence-level view for the final polish. Moving through the landscape of her words, she accepted subtle suggestions from her digital partner – a tighter phrase here, a clearer transition there – each refinement adding punch and clarity. A last, automated sweep smoothed out the few remaining grammatical bumps and banished elusive typos, leaving her with an article that felt both deeply hers and collaboratively elevated – structured, engaging, and ready to inspire mindful journeys.

The Work of Writing in the Age of AI

Do these examples impress you? Or is this already what your workflow looks like? What if I told you that, with the exception of the third scenario, I’m actually describing features that already exist? In fact, I had AI research some current AI writing products and asked it to paint a futuristic picture based on those findings.

We’re just at the doorstep of an incredible evolution, and things are only getting better and faster! I truly believe that the future of technology will surpass our wildest dreams, guiding us toward possibilities we haven’t even begun to imagine.

What will characterize the work of writing in the age of AI? This is an open question for sure. While I have some thoughts on the matter, as I’ve shared above, these ideas are still in need of validation. This process itself is a journey of writing, where initial seeds of thought develop and blossom into something truly beautiful. Despite the uncertainties that lie ahead, I feel confident about a few key points:

AI will play an increasingly vital role in writing, evolving from a simple proofreader and research assistant to a fully-fledged apprentice writer—much like the apprentices that Renaissance painters often employed for their grand works—and eventually a worthy collaborator (maybe we should call it ghost writer).

The model for AI as a writing collaborator can be found in coding. If vibe coding has become a thing, then why not vibe writing?

Of course, there will be widespread concern regarding authorship, which will ultimately lead to a redefinition of what it means to be an author. It may shift from being the one who simply crafts the words to the one who generates the ideas behind them.

P.S.

Here are some current tools that harness the power of AI to facilitate if not transform writing. I’ll share them below, and I’d love to hear if you come across any others!

Dedicated to fiction writing: https://sudowrite.com; https://www.novelcrafter.com; https://www.squibler.io Academic focused: https://paperpal.com General purpose: https://www.effie.pro; https://rytr.me Business oriented, GTM: https://www.copy.ai; https://www.jasper.ai; https://www.anyword.com